I have seen the future of art. I wasn’t expecting it and I certainly didn’t anticipate it coming from the mouths of talking teddy bears, but such are the cumulative quintessences of kismet and epiphany. Ephemeral. Ethereal. Evanescent. Temporal. All exists in the moment. Like a room full of talking teddy bears venting their deepest, darkest secrets.

Eighty of them. Eighty Teddy Ruxpin toy teddy bears offering sentiments and observations from a wide spectrum of emotional perspectives. Well, a spectrum twenty-four emotions wide, actually. And not wide so much as a conical vortex of colliding feelings and sensations. And then there’s the amorphously abstract dreamlike sound track.

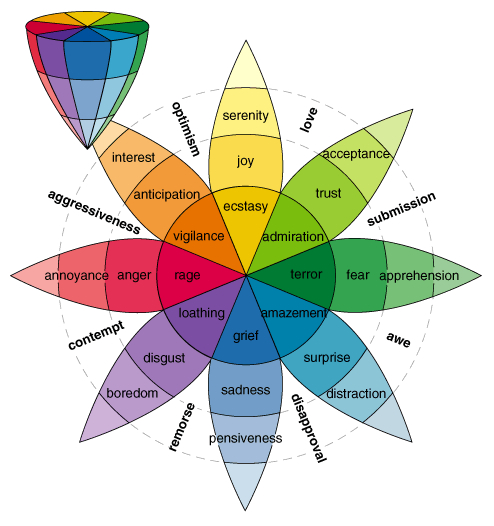

The talking teddy bears are the stars of a project referred to as T,E.D.—which stands for Transformations, Emotional Deconstruction. It debuted as part of the BYTE ME 2012 exhibition at Launch Pad Gallery (http://launchpadgallery.org/), on January 6th. The press release describes the production as a “large work [which] features 80 customized Teddy Ruxpin dolls wired together, delivering real-time emotional content from the internet in discreet 1-minute ‘packages’ based on the Emotion Wheel developed by the psychologist Robert Plutchik. Additional interactive real-time input can also be received from text messaging or an on-site user interface.”

Whew! Okay, fine.

T,E.D. is the brainchild of conceptual artist Sean Hathaway, with Carlos Severe Marcelin of Sally Tomato providing the imaginatively unique soundtrack. The result of their collaboration is a technological achievement of some dense specific gravity, the ramifications of which extend exponentially throughout the art and music worlds, their impact not yet fully determined.

It’s probably been 25 years since the real heyday of the Ruxpin empire. For those unfamiliar (and I’m no expert, to be sure), the Teddy Ruxpin line were the teddy bears of choice for discerning four-year-olds in the mid-80s. The cache was that the Ruxpin bears talked. They told stories. They moved their eyes and mouths as they told stories. With the mere slip of a cassette into the accessible backside port, the toys could change their stories, and ostensibly, change their limited range of facial expressions as well.

And so the technology slumbered for two decades, until 2005, when Backpack Toys produced Teddy Ruxpin 4.0, which finally exchanged analog technology for thum thar new-fangled digital ROM cartridges. But Backpack eventually discontinued production and the remaining dolls were left to languish in outpost warehouses scattered around the nation. There is nothing so inexpensive as load of unwanted Teddy Ruxpin dolls. But alas, there it is.

When Sean Hathaway was just a kid, Teddy Ruxpin was all the rage. He says he was “scared of those bears…for their vague and gross mechanical representation of a living thing.” Considering what he ended up doing with the bears, that’s a presciently fortuitous choice of words.

What inspired his experimentation with Teddy Ruxpin dolls, anyway?

“Having a palette of Teddy Ruxpins in my basement,” he giggles.

Well, yes. That would seem to be a determining feature: a basement full of teddy bears.

“There was this old surplus store called Wacky Willie’s—it went out of business. They’d had these for years. I’d been looking at them since I was a kid. And I said okay, I’ll give you twenty-five cents apiece for them. I got a hundred of them, so…”

A hundred. Sure. Who’d ever pass up the opportunity at a hundred Teddy Ruxpin dolls? A no-brainer. And so how long has Sean been working on this venture?

“Off and on for about three years. It’s just been my evening project. It started out like ‘what am I gonna do with all these dolls?’ But it started to take on a life of its own. I could make them talk. Okay, now that I can make them talk, what are they going to say?”

Yeah. Now that you can make them talk. Way way way…Wait a minute. “Make them talk?” “What are they gonna say?” Is this going to be like one of those stories you hear about where some Asian porn flick is coming out of the mouths of Ruxpins, or something like that?

Hardly.

“I was playing around with voice synthesis and realized I could get basic info about phonemes, which I could use to animate their mouths in sync with the speech synthesis. So now I have this creepy sort of animatronic puppet that’d speak any text I give it. Okay, that’s pretty fun but now what should it say? What’s worth saying? Then I remembered the excellent web site /online art piece www.wefeelfine.org by Jonathan Harris and Sep Kamvar, which aggregates emotional content out of people’s blogs in real time. They invite other artists to use their data and offer a mechanism to query it.”

Uh, aggregates emotional content? Gee…

“That part just came about on its own over time. At first I started with a bunch of bears that I wanted to make sing in some sort of chorus. I thought maybe an opera where the bears would burst into flames as characters died. But as I explored the bears and technology, and as I made some fortunate mistakes playing with them, they presented me with a series of decisions that led to the final piece.”

The www.wefeelfine.org site is a work of genius in its own right. Their manifesto states:

“Since August 2005, We Feel Fine has been harvesting human feelings from a large number of weblogs. Every few minutes, the system searches the world’s newly posted blog entries for occurrences of the phrases ‘I feel’ and ‘I am feeling’. When it finds such a phrase, it records the full sentence, up to the period, and identifies the ‘feeling’ expressed in that sentence (e.g. sad, happy, depressed, etc.). Because blogs are structured in largely standard ways, the age, gender, and geographical location of the author can often be extracted and saved along with the sentence, as can be the local weather conditions at the time the sentence was written. All of this information is saved. The result is a database of several million human feelings, increasing by 15,000-20,000 new feelings per day. Using a series of playful interfaces, the feelings can be searched and sorted across a number of demographic slices, offering responses to specific questions.”

If you’re asking yourself, “Gosh, I wonder if this technology could be used for evildoing?” you and I are on the same page. And that’s just the tip of the creative emotional sno-cone in this particular case. There’s much more to the story. Robert Plutchik’s Emotion Wheel.

Robert Plutchik conceived of a system for exploring the full range of human emotions and how they are related. In 1980, he developed a twenty-four-color, two-dimensional, emotion “wheel,” as well as a three-dimensional conic version, to illustrate the complex inter-relationship between positive and negative emotions, demonstrating that human feelings were an intricate combination of emotions. A veritable rainbow stew.

In Plutchik’s system there are eight principal emotions, four pairs of polar opposites, found at the primary and secondary intercardinal points of the wheel: Joy/Sadness and Fear/Anger at the primary points. Trust/Disgust and Surprise/Anticipation at the secondary points. The three primary colors/emotions are: Red/Rage, Blue/Grief, and Yellow/Ecstasy. Everything else builds from there, I guess. Seems reasonable. Pretty much covers it in my world.

Though innovative, Plutchik’s union of emotions with colors was, obviously, not a novel idea. Red with rage, blue with sadness, and green with envy have been with us since…since colors and analogies, I suppose. Similar correlations to the western musical octave and the twelve-tone scale are certainly appropriate, although as yet not fully explored, as far as I know. And then there’s the Lüscher-Color-Diagnostic, of course. Put that all together and you’ve got a real concept, although I am unable to conceive of it at this time.

But with three intensities of eight spectral colors (there are two shades of green in Plutchik’s spectrum), all primary, secondary and tertiary colors and related hues are represented, twenty-four in all, twenty-four gradations of emotions, each within fifteen degrees of the next. There are a few specialty items, such as a very pretty, salmon-colored “Annoyance” and a verdant, meadowy, chartreuse “Acceptance.” But all the color/emotion combinations seem to fit, somehow. Pastels. Mix and match colors and emotions and you’ve got Freudian Feng Shui 101. Is that a thing? Sign me up.

How did the Plutchik Emotion Wheel come to play in Sean’s grand design?

“Close to the end of the initial concept development I knew I wanted Ted’s performances to be self-generative based on what was happening emotionally online at any given moment, but I found that just letting it run in a totally random way was really confusing and displeasing. I didn’t want to force or drive what the installation was doing as that would kill the generative aspect of it. So I needed a way to enforce a set of basic rules from which just the right amount of order would emerge out of an otherwise cacophonous mass of content.”

We all hate those cacophonous masses of content.

“Since I was working with emotional content an emotional classification system seemed a natural choice. And after reviewing a few different constructs, the Plutchik schema seemed to be the most natural and intuitive one. It allows for an infinite array of subtle emotional expression while still maintaining a simple and atomic foundation that worked very well for setting up a simple classification algorithm that would give the piece its randomness—its lacking sense of underlying order.”

Dude. What the hell are you talking about?

“It was the music Carlos composed that really brought this part to life. I had originally intended to have a series of several five-minute-long background musical pieces to accompany the speech, but with the Plutchik scheme this rapidly evolved into a set of twenty-four one-minute pieces on a single theme that represent each of the twenty-four foundational emotions in the Plutchik schema.”

So it’s like a real-time play. But, I’m not sure how that differs from real life. Isn’t life a real time play, after all?

“The product is a generative installation that drifts about through whatever emotional states are most pervasive at any moment but presented as an endless stream of doglegging one minute sets where not only the content within the set is relational, but so is the underlying musical theme backing it up.”

Okay: it’s real life with a musical soundtrack, then. Obviously, Sean comes from an extensively hardwired electronics background, right?

“I didn’t have any experience with electronics in the beginning, but learned what I needed to in order to put the project together. My education is mainly scientific and technical in nature and I think that puts me at a slight advantage to be able to pick-up on new technical skills at a fairly rapid rate. Over the past few years, I have been greatly inspired by sources such as Make Magazine and www.instructables.com/ that provide a venue for sharing knowledge and skills. There’s a growing collection of open-source software tools, and collective skill-sharing clubs.”

Sean makes it sound like pretty much anybody could fill a room with inanimate teddy bears, make them talk, give them facial expressions and emotions culled from some bunch of guys “harvesting human feelings” and make it work in real time with an unusual music soundtrack in accompaniment. Really?

“It’s possible for any novice hobbyist or artist to do vacuum forming, 3D printing, physical computing or in my case designing a circuit board that could be sent to a fabrication shop for production. Just click a button to send the files, and two weeks later, you have a hundred circuit boards showing up in the mail ready for you and your friends to start soldering parts to. It really is an amazing time to be a maker of things.”

Vacuum forming? 3D printing? What’s “physical computing?” Circuit board design? You bet. Sounds like no big deal. Just make things. No problem. Run it. But, what does it all mean? What do all these emoting bears say about the human condition?

“To me the piece represents a celebration of a global level of human emotional expression that would not be possible without the technological age in which we live. These are tough questions. Our species is on a steppingstone of the evolving Information Age. Each of us has the ability to broadcast and share every part of our lives with nearly the entire world community. Like Dylan said, ‘ten thousand people talking but nobody listening’, but it’s really more like a billion people talking. I guess that’s a big part of what I was trying to say with this. I wanted to pull pieces of this collective state-sharing out of the void and give it a real presence and audience.”

Doesn’t it all seem sort of lonely and impersonal?

“Everything you hear in the installation is something that somebody somewhere in the world wanted you to hear. Right at this moment somebody in Montana has lost a love and someone in New Jersey has found one, and they want you to know about it. Isolation of one form or another is universal human truth. But how is that truth altered by such complete and intimate connectivity? That’s a question I ponder quite a bit when thinking about this installation.”

Well, the world has changed pretty dramatically over the past 20 years. There’s no denying that. It’s hard to say where it might go from here.

“I constantly contemplate the notion that my one-year-old daughter will never know a world where she can’t share how she feels about the bowl of soup she’s eating with people in New York, Paris, Bangkok or Tokyo—before it has a chance to get cold. But what does that mean exactly? Will anyone be listening or care? I do feel pride and a greater sense of connectivity to humanity knowing that when someone’s daughter somewhere in the world was pleased with her bowl of soup, for a small group of people on a Friday night in Portland, Oregon, that message was received loud and clear and for at least a moment acknowledged.”

Picture a darkened room, maybe about the size of your living room. On two adjacent walls eighty teddy bears are hung in neat rows, all linked by a network of thin wires. Suddenly a spotlight shines on one of the bears, and it opens its eyes, begins to move its lips and to speak, sounding a bit like Stephen Hawking. It expresses some vague feeling of distress in that robot-voiced monotone, then the spotlight is extinguished to light upon a different teddy, where the voice of, say, Australian Karen GPS lady conveys a gathering sense of anxiety. A British-voiced male teddy bear, like the Beatles’ “Number 9” guy, makes a brief, succinct statement and vanishes. HAL enters the scene and registers to any “Dave” his wary apprehensions. It’s a familiar cast of characters. The juxtaposition of cheery Ruxpin faces and morbid human sensibilities makes for a jarring experience among all who witness.

Meanwhile, Carlos Severe Marcelin’s cinematic soundtrack whirs and whines enigmatic dejection in one instance, orchestrates desperate symphonic alienation in others. The experience is very much like being inside a Luis Bunuel film, with Federico Fellini directing. Even though they are lifeless bears whose eyes and mouths are responding to mere electrical impulses, their sentiments are all too human, desperate for contact and intimacy. To stand among all those bears baring their souls—like a Ruxpin AA meeting—is a surprisingly wrenching encounter. Hypnotic. Haunting. It’s nearly impossible to walk away from the exhibit without having a visceral response.

Out in the vast expanse of world, at any moment, millions and millions of people are transmitting their impressions online, to be culled and categorized into segmented channels like an emotional Pachinko machine. It would never occur to anyone to think that their random introspections might be transformed into the script for two walls of talking teddy bears. But as Sean Hathaway said:

“For a small group of people on a Friday night in Portland, Oregon, that message was received loud and clear and for at least a moment acknowledged.”

Find me dimstricken. Where next? Okay, all right then, so what color would Sean be on the Plutchik wheel? What would his bear say?

“I would have a blue-green color [Surprise and Apprehension, perhaps?], and my bear would say: ‘I feel humbled that my work was as well received as it was’.