Led Zeppelin III

Led Zeppelin III

Severe Recordings

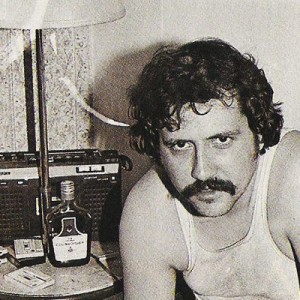

It was in November of 1970 that notorious bon vivant and ferociously cranky rock critic Lester Bangs called Led Zeppelin the “ultimate Seventies Calf of Gold.” This was in the eleventh month of the first year of that decade, mind you. He wasn’t wasting any time. This proclamation came in reference to Led Zeppelin III , which he was reviewing for Rolling Stone. And none too favorably.

Their third album deviates little from the track laid by the first two, even though they go acoustic on several numbers. Most of the acoustic stuff sounds like standard Zep graded down decibelwise, and the heavy blitzes could’ve been outtakes from Zeppelin II. In fact, when I first heard the album my main impression was the consistent anonymity of most of the songs — no one could mistake the band, but no gimmicks stand out with any special outrageousness, as did the great, gleefully absurd Orangutang Plant-cum-wheezing guitar freak-out that made “Whole Lotta Love” such a pulp classic.

In his defense, Bangs did go on to offer faint praise for a couple of songs as being “not bad at all.” And he was especially fond of the tender ballad “That’s the Way,” wherein “Plant sings a touching picture of two youngsters who can no longer be playmates because one’s parents and peers disapprove of the other because of long hair and being generally from ‘the dark side of town’.”

Through the dark glass of retrospect, some forty-three years later, that Zep album, in particular, is universally recognized as something of a turning point for the band. It set them free from the strictures of the blues—which had been their lot as the “New Yardbirds” of their first two records. It pointed the way toward the epic songs that were soon to follow: “Stairway to Heaven,” “Battle of Evermore” and “Kashmir” and all the others that incorporated traditional folk and middle Eastern music in new and unique ways that are still revered today.

Lester Bangs couldn’t have foreseen at the time what would fully follow with the legend of that band or with music in general. He died in 1982, just before the children of Zep (Van Halen, Metallica, Scorpions, etc) came into full recognition. That bunch was followed by another generation, ie Guns and Roses, and, uh, Kingdom Come, Black Crowes, Soundgarden, Stone Temple Pilots, and Porno For Pyros.

After them, yet another generation was begot in 21st century bands such as Wolfmother, White Stripes, Black Mountain and Rival Sons. It would seem Lester didn’t fully anticipate the extensive herd that Seventies calf of gold would propagate—before their reign was abruptly terminated with drummer John Bonham’s death in October of 1980.

I first ran across Sally Tomato (named after a character in Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s) back in the summer of 2001 when I reviewed their debut album, Soup, for Two Louies—a recording that knocked me out for its originality and flair for the unique. I knew of Carlos Severe Marcelin. Before Sally Tomato he had been a guitarist for the folk/rock band Silkenseed, who put out a couple of albums in the ‘90s.

When Silkenseed broke up, flautist/vocalist Monica Arce retired to parenthood, as her husband guitarist Edwin Paroissien and vocalist Hamilton Sims went on to form Little Beirut, while Carlos and drummer Eric Flint joined vocalist Toni Severe Marcelin (Carlos’ wife—whom most know to be Sally herself) to create Sally Tomato.

In the years since their inception, in addition to releasing conventional recordings, Sally Tomato have regularly pursued non-traditional projects. In 2008 they produced the semi-autobigraphical rock opera Toy Room, which they performed that spring for three nights at the Wonder Ballroom, involving a cast and crew of many dozens. Critics deemed the musical’s effects “Bjorkish,” and the concept and production comparable to a “female-centric version of Tommy.” Combine those two elements and you have a good idea of the impact of the play. The DVD version of Toy Room has won awards at prestigious film festivals all around the world.

Last year Carlos and drummer Eric Flint, “Sally Tomato’s Pidgin,” created an ambitious instrumental album, The Planets. That album served as a showcase for both musicians’ precocity, as well as a primer into the machinations of our very own solar system. For that release the band assembled a performance art installation, which they displayed for one day at Buckman Park in southeast Portland.

After preparations for a film were shelved for the time being, the Marcelins and Flint began looking for a new project for Sally Tomato. Last spring they hatched the plan to record Led Zeppelin III in its entirety. Now, there have been countless Led Zep “tribute” ventures over the past few years, just in Portland alone. And that’s great. There cannot be enough Led Zeppelin tributes.

But, typically, there are two approaches to such things. The first and most common is to find a guy who sounds and/or looks like Robert Plant, learn a bunch of Zep songs and put on a show “bringing back the live experience,” etc. The second method is to gather a bunch of acts together and have them do their interpretations of Zep songs. Both techniques have their obvious advantages and flaws.

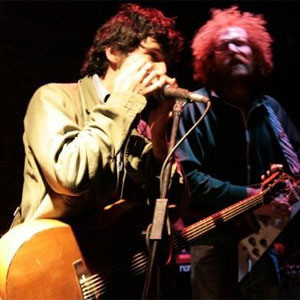

Sally Tomato decided upon a third strategy. With Carlos performing as Jimmy Page and Eric as John Bonham, the duo pretty much re-recorded Led Zeppelin III in the Tomato basement studio. The guitar tones are spot on. Execution near flawless. Other musicians were brought on board, as were needed, to fill out the occasionally complicated orchestration. Owing to the expert musicianship, the resultant instrumental recording is very close to the original in every way, without being a mere copy.

What the band chose to do at that point was something very unusual and it turned out to be a great decision. They brought in guest vocalists to sing Robert Plant’s parts. The result is that every song is instantly recognizable by its accurate instrumental environment. But then some other voice starts fronting the band. In most cases that voice is drastically different from Bob’s.

In some instances that voice is almost better suited to the particular song than Bob’s. It’s utterly familiar music you’ve never heard before. This is not a tribute album. Not in the least. This is Led Zeppelin III. But Robert Plant took a holiday for this version. So John, Jimmy, and John Paul invited friends over to do the job instead. This album certainly stands on its own merits and rivals even the original for impact.

Besides Sally herself, Carlos sings a song. Steve Wilkinson of Wilkinson Blades makes an appearance. James Faretheewell (of the Foolhardy) jumps in for a song. Former Silkenseed bandmates Hamilton Sims, Edwin Parroissien (of Little Beirut) and Monica Arce take turns at the mic. And Drew Norman (Professor Gall, Porcelain God, Cowtrippers) commands the spotlight for one song, as well as adding banjo and an array of guitars to several other songs. Among modest appearances by numerous guest musicians, Ben Schroeder is the key musical addition, contributing mandolin and violin to a couple tracks, and rock solid bass throughout.

In an A/B comparison of the original with this version, the first thing one notices is that compression has come a long way over four decades. Engineer extraordinaire Dave Friedlander (see Pink Martini review last month) positively slams the mix for “Immigrant Song,” actually generating more power than Zep could muster (in 1970). The only thing missing instrumentally is a little tremolo-laden figure Jimmy lays in places on the right. Otherwise, this is it. Sally, supported by the eleven member Valkyrie Choir, gives the vocal a decidedly feminine perspective, but in the same vocal range as Bob’s “orangutan Plant” bellering.

The Tomato take on “Friends” is a slight variant, perhaps like an outtake. Schroeder’s violin is different in texture from the thicker violas found in the primary model. Sally’s vocals and the Valkyrie Choir lend the song a more ethereal component not heard in the Zep rendition. Friedlander’s magic is clearly evident here, with tricks at his command only dreamt of in those primordial days of rock. He adds subtle effects that contribute greatly to the otherworldly nature of the cut. Very cool.

“Celebration Day” lacks a bit of the hectic, sloppy urgency of its predecessor. Sally’s vocal actually seems like an improvement over Robert Plant’s (her pitch is better). He sang the song at the uppermost range of his voice, sounding pinched and whiny. A woman singing in that register is not nearly so annoying, although no Zep head worth his salt would ever own up to that shortcoming in our golden boy’s vocal arsenal. Carlos carries out the prototypical Pag-ian pyrotechnics with characteristic aplomb. And Flint’s Bonzo excursions are certainly worthy attempts (if considerably less alcohol fueled), though far less squeaky.

Things heat up quickly with “Since I’ve Been Loving You,” the song the Zeps found one of the most difficult to render when they recorded it (essentially) live in the studio. Full disclosure, truth in music reviewing be told, I played the elementally innocuous organ part on this track—and it is obvious from the start that I don’t hold a candle to John Paul Jones’ classical training. Fortunately, Ben Schroeder’s bass more than adequately handles JP’s pedal work to rescue the day.

And in the end it’s probably just as well—as Carlos and vocalist Steve Wilkinson need all the sonic space they can get. Wilkinson absolutely melts the ones and zeroes with his searing interpretation of the lyrics. His is different, even darker than Robert Plant’s reading. Steve clearly makes the song his own (who’s this Robert Plant guy anyway?), wringing raw power and passion from every phrase, every guttural utterance.

Carlos’ molten guitar excursions rival Page’s for intensity. In the extended intro solo Jimmy rushes the timing before settling in with a fiery burst. Carlos is more of a controlled burn, soulful in tone and relaxed in implementation, calling to mind Carlos Santana.

Jimmy’s solo in the middle is considered one of the greatest guitar displays ever rendered in recorded music (check out what he does—rather effortlessly—around the 4:00 mark). That solo alone made of the song a staple of the band’s live shows for many years. Carlos holds his own in that battle, though his style is different and not nearly as blues centered as Page’s always was. Still, in the end the Tomato version of this Zep chestnut is certainly radio-friendly on its own terms, because of Carlos and Steve. It kills!

Carlos takes over the lead vocals on a groovy little excursion through the riff heavy “Out on the Tiles.” His sneaky, snaky cool delivery is an octave lower and diametrically opposed in demeanor to that of Robert Plant. The Valkyrie Choir return for the memorable sing-along chorus. Oh yeah, oh yeah, oh yeah-ah. A fun romp.

A number derived from some of what Lester Bangs called the “acoustic stuff,” that has stood the test of time is “Gallows Pole.” Without the help of the internet, Lester probably didn’t know the centuries old history of the song (“The Maid Freed From the Gallows,” “Child Song 95”). The Tomato’s version is a bit shorter, with a bit less country jam. Still, it’s quite spectacular, nonetheless.

Hamilton Sims fronts the procession, with Carlos on acoustic guitars and Ben Schroeder on mandolin and bass. Sims’ treatment is mellower at first, more quietly desperate in seeking his redemption. He begins the song an octave lower than Bob’s torn sheet shriek, before jacking things up midway to a fevered plea—Friedlander adding ghostly effects to amplify the impact.

Locomotion gathers increasing steam, with Flint joining Drew Norman as he steps in to pluck a banjo sprint over agitated electric guitar comping—provided by fourteen-year old Keelan Paroissien-Arce (Edwin and Monica’s daughter). Coming down the homestretch, Keelan knocks out a gnarled solo, portending for the foreseeable future a positive outlock for rock and roll.

The Tomato rendering of “Tangerine” is actually something of an improvement, in that Carlos is perhaps a bit more focused in the implementation of his guitars than Jimmy Page was when the song was originally recorded—the instrumentation and production are much cleaner. Edwin sings the lead vocal, joined by Monica for the high harmonies in the chorus. Edwin’s treatment adds a wistful quality and a boyish longing to the context.

Carlos nails the 12-string guitar motif—though with electric instead of acoustic—that yields to the harder middle section (a harbinger of “Stairway to Heaven”). Drew Norman returns with flamethrower lap-steel guitar in the soaring solo (calling to mind Duane Allman), exceeding even the Pagemaster himself in sheer awesome force. Riveting. Schroeder’s hard-driving bass and Flint’s adamant drums propel the production forward. It’s another stellar performance, unique, yet instantly familiar and contemporary.

The band handles “That’s the Way” in similar fashion: a loving laudation with just enough special detail to make the arrangement quite distinctive in its own right, without departing far at all from its model. What’s different here is precisely what makes it special. Sally and Hamilton Sims share lead vocal duties, poignantly alternating verses. In the process they transform a “touching picture of two youngsters who can no longer be playmates” into a song about star-crossed young lovers—a moving duet between Romeo and Juliet.

She sings “I don’t know how I’m gonna tell you/I can’t play with you no more/I don’t know how I’m gonna do what mama told me/My friend, the boy next door,” to which the heartbroken lad despondently replies “When I’m out I see you walking/Why don’t your eyes see me/Could it be you’ve found another game to play/What did mama say to me?”

The instrumental components here are identical to the antecedent. Over Sally’s introductory intonations, Carlos’ acoustic guitar is matched with Schroeder’s mandolin and Drew Norman’s lap-steel guitar—more mournful and less busy than Jimmy Page’s. The aural composition is earthier, less airy and dry. Very nice.

After Carlos deftly glides through the fingerpicked mastery of the extended intro (on electric rather than acoustic guitar), Norman steps forward for the scrappy tour de force “Bron-Y-Aur Stomp.” Invoking his Professor Gall personae Drew commands the vocal voodoo voogum with a bit more gravity than Plant’s more tentative assertions. He sets the mojo to “Stun,” working against his slithery resonator guitar (a perfect addition to the setting), pounding swamp stompbox, and the insistent march of Flint’s militant snare. Though not that far from the Zep edition, there are a lot of minor features in this presentation that are decided enhancements: specificially Drew’s gruff vocal and the delta guitar phrasings. Great.

Finally, what was a throwaway for Zep, the traditional blues-based “Hats Off To (Roy) Harper,” with just Page on bottleneck acoustic guitar and Plant on muffled harp-mic vocals, is transformed into a hard rocker with a sunny California sound. After a brief introductory interlude reminiscent of Dominic and the Dominoes’ take on “Little Wing,” James Faretheewell comes on like Sky Saxon riding tandem with Mike Love on a psychedelic surfboard, mumbling soulfully over the old I-IV-V.

The middle breaks sideways into a spoken word interlude (recited by Reverend Tony Hughes of Jesus Presley) called “I Hate the White Man,” written by the actual influential British musician, Roy Harper to whom the Zep song is dedicated, before veering back onto the Pacific Highway. Of the ten, this song sounds the least like the masters—not so difficult, seeing as how it didn’t have much of an identity to begin with.

Lester Bangs aside, Led Zeppelin III now stands as a groundbreaking album. It brought into clear relief aspects of English traditional music performed in a rock setting, a milieu soon imitated by the likes of Jethro Tull, Steeleye Span, Yes, Strawbs, Genesis and a host of others who used elements of British folk music in their presentations to greater or lesser degrees. Ultimately this album is father to all that.

In it’s primordial state, the parent album is a little loose. Performances are occasionally sloppy or spontaneous, or both. But the spirit of invention—especially present in Jimmy Page’s inspired feats of musical majesty are indelibly inscribed upon the pillars of rock and roll.

Some might perceive an effort to reproduce that album to be an act of naive hubris. But, performed from a perspective of profound reverence and respect, there is genius here. Sally Tomato and Friends didn’t copy the original so much as assimilate it. They have made it their own and reconfigured, while never losing sight of the original blueprint. The arrangements, while instantly familiar, are not identical when compared directly. There are alterations and enhancements along the way—vocals being chief among them, but not the sole instances of divine kismet.

Led Zeppelin III is not a simple tribute album, but a sincere homage honoring the innovation that the original version spawned. What’s old is new again. And this recording neatly bridges the many years between old and new in inventive ways, panegyric to a legacy that seems secure for generations yet to come.