Play:Songs From Shakespeare

Play:Songs From Shakespeare

Refrigerator Records

Considered to be perhaps the greatest wordsmith in all the English language, not much is known about William Shakespeare. What is known about the man is often clouded by rumor and innuendo. But as time passes the only conclusion at which one can reasonably arrive is that Mister Shakespeare actually authored the thirty-seven plays (that we know of) for which he is renowned—and not Christopher Marlow, Francis Bacon, Walter Raleigh, Edward de Vere or the dozens of other characters who have at various times been briefly nominated for the achievement.

It wasn’t like Shakespeare was a complete unknown back then. By the time he was twenty-eight, he was already garnering damned faint praise from his fellows, such as this silver tongue-twister from dramatist Robert Greene in an industry rag called the Stationers’ Register: “…There is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tiger’s heart wrapped in a Player’s hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country…”

Except for the fact that a “Johannes factotum” might also be called a “jack of all trades,” I have no idea what half of that means, but it seems likely that Greene’s readers did, which in and of itself should give you a clue that the average cleat was a tad better educated than most of the upstart crows we see coming out of high school today. Those kids took Latin and knew of the Classics, whereas most of today’s students major in Video Games and Android Attenuation, bombasting tweets to their hale and hearty fellow bros at all hours.

The guy was no slacker. In fact, Shakespeare, who turned a spry four-hundred and fifty years old earlier this year (though he doesn’t look a day over three-hundred) was a pretty wealthy guy by the time he was thirty-five years old. He had a lot going on. For one thing, he wrote all those plays and they were pretty popular at the time (though he probably didn’t get any royalties on any of it to speak of). He owned a chunk of the Globe Theater and the acting company that performed there. He owned a couple of houses. He had a wife and kids. Hell, the family was issued its own coat of arms, fer chrissakes. They were doing okay.

And while William Shakespeare is best known for his plays, and to a lesser degree for his sonnets, few give him much credit for being one of the better songwriters of the Elizabethan era, right up there with William Byrd and John Dowland, the madrigalists and other pioneers of the craft, who were churning out the hit consort tunes of the day. Check out this famous ditty from The Tempest: “Where the bee sucks there suck I/In a cowslip’s bell I lie/There I couch when owls do cry/On the bat’s back I do fly/After summer merrily/Merrily, merrily shall I live now/ Under the blossom that hangs on the bough.”

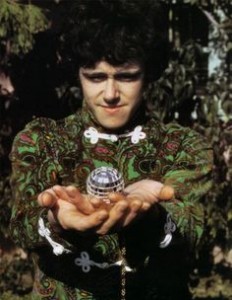

Now that sounds just like something Ian Anderson might have thrown down for a late ‘70s Tull album. As a matter if fact, As You Like It generated several hit songs. Composer Thomas Morley, a contemporary of Shakespeare, is known to have written the music for a song or two in that and a few others of Shakespeare’s plays—most notably “It Was a Lover and His Lass.” The 20th century’s own Donovan set the familiar “Under the Greenwood Tree” to music, though not particularly well.

“Under the greenwood tree/Who loves to lie with me/And turn his merry note/Unto the sweet bird’s throat/Come hither, come hither, come hither!/Here shall he see/No enemy/But winter and rough weather.”

One of the more ambitious attempts to delineate Shakespeare in a new and inventive way, arrives to us via Here Comes Everybody. Here Comes Everybody? You ask. Shouldn’t they be doing an album about Finnegan’s Wake? What does Shakespeare have to do with James Joyce? Plenty. He’s all over Joyce’s Ulysses. He is the main subject of discourse in Chapter Nine. And he makes a brief guest appearance in the “Nighttown” chapter wearing a reindeer antler hat rack crown.

And what does Joyce have to do with Here Comes Everybody? Finnegans Wake! The band is led by HCE, Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker and his lovely Liffey-rivered wife, ALP: Anna Livia Plurabelle—though they both go by many aliases, ie Ancient Legacy of the Past and Here Comes Everybody. No wait. That’s Joyce. Here Comes Everybody, the band, is helmed by drummer, vocalist Michael Jarmer and his wife Rene Orme-Jarmer, a talented drummer in her own right and quite an accomplished keyboardist and vocalist as well.

The Jarmers formed HCE back in 1986 and have recorded, jeez I don’t know, ten? twelve albums over that time. I’ve reviewed most of them. I remember that Michael drummed with Incognation on a bill with my band at the Fat Little Rooster in 1983. And Rene actually auditioned as a drummer for my band around the same time. All this to say, that despite their youthful appearances they go back thirty years in the Portland music scene. And they’ve played with an impressive array of side players along the way.

Both of them are teachers, so they have respectable jobs, besides their artistic endeavor. They’re well-rounded. And Michael’s an English teacher and an author. He published Monster Talk a couple of years ago, a novel about a descendant of Doctor Frankenstein’s “experiment.” Rene teaches private drum lessons and coaches the drum line at Rex Putnam High School. These guys are not lightweights.

Which is why, in the scheme of things, this present undertaking comes as no big surprise. It’s literary. Yeah? Well everything HCE have ever put out has had a literately literary element at play. Lyrically, Michael is witty, cheeky, erudite. Cerebral. So it’s no big leap having Willie the Shake in to write (most of) the words here. The genius here is that the Jarmer’s reworked the Bard’s material into a new narrative, a “play” (in two Acts) as it were, constructed out of lines extracted from only three of Shakespeare’s plays—Hamlet written later in his career, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet, which were earlier works.

Hamlet is larded with an array of songs in its own right, many of them sung by crazy Ophelia or vocalized by troubled Hamlet to make everyone think he was crazy. But for the most part those songs are left alone, with new connections being made from chunks of monologues, soliloquies and orations.

Take, for instance, the pretty “What a Piece of Work,” cut from the whole cloth of Hamlet’s monologue in Act 2, Scene 2, written not in typical Shakespearian iambic pentameter, but in blank verse. “What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty! In form and moving how express and admirable! In action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god!”

In the verse this plays out on a narrow musical bed. Over Michael’s kinetic drums and confident vocals, Rene layers warm tufts of electric piano, while longtime bassist David Glide here makes his first of four guest appearances, accentuating Rene’s left hand. The chorus, which are Hamlet’s next two lines, “The beauty of the world. The paragon of animals,” opens up majestically. Ethereal background vocals support Michael and Rene in lead duet. Indistinct orchestration in the periphery creates a wistfully nostalgic, haunted turn, a longing in the delivery of the phrases.

The concluding lines of Hamlet’s brief speech serve as the second verse—Michael’s reading as ambiguously jaundiced as the first—again perhaps exalting the lofty righteousness of Mankind. Maybe. But the return to the chorus blankets such bluster with a relentless agenbite of inwit. “I have of late…lost all my mirth.”

A ballad, “The Advice Song” floats upon Rene’s misty major 7th chord inflections on electric piano, calling to mind one ‘60s Burt Bacharach song or another, circa Herb Alpert. The “advice” is extracted from Polonius’ lecture to his son, Laertes, in Act 1, Scene 3 of Hamlet. A former advisor to Hamlet’s dead father, the king, (also named) Hamlet, Polonius fancies himself the wise mentor, but whom Hamlet the younger considers to be among a league of “tedious old fools.”

In this instance, Polonius dispenses some of his most memorable homilies, many employed in Michael’s adaptation of the speech—which builds its chorus on the memorable line “to thine own self be true.” Rene adds lush string settings at the edges and Al Torres neatly contributes a well-placed trombone solo that hits with just the right amount of irony.

The Beatlesque “The Play’s the Thing” nicely captures Hamlet’s soliloquy at the end of Act 2, Scene 2, wherein he plots his revenge on his uncle Claudius, brother to the slain ruler, who has taken over the throne and taken up with Gertrude, King Hamlet’s widow, Prince Hamlet’s mother. Over an 11/8 (?) latin jazz rhythm, provided by Rene on drums, Michael delivers the first verse sounding very much like Paul McCartney, singing “…Hum, I have heard/That guilty creatures sitting at a play/Have, by the very cunning of the scene/Been struck so to the soul that presently/They have proclaimed their malefactions.”

The chorus straightens out into a straight-ahead gait, Michael and Rene singing “the play’s the thing/Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king,” faintly calling to mind Pink Floyd’s “Us and Them.” Rene’s piano and strings orchestration and Dave Captein’s punchy bass work add a Phil Specter-like Let It Be ambiance to the sonic atmosphere.

“Song of Indecision” knits together Hamlet’s end of a conversation with Ophelia in Scene 1 of Act 3, where he seriously fucks with her fragile head. He loved her once. He loved her not. Hamlet is a complex guy and maybe a brick or two short of a retaining wall. But the scene concludes with Hamlet chiding poor Ophelia, urging her to “get thee to a nunnery,” the hook line for the chorus.

The song could pass for a Bowie arranged Killers song and Michael renders a Brandon Flowers-informed vocal. But more than that, this song sounds like classic Here Comes Everybody, with Rene’s dappled keyboard phrasings glistening against bowed double bass in the chorus, Michael’s persistent beat and Glide’s galloping bass.

Hamlet’s consummate encounter with Claudius in Act 4 is the basis for “Where’s Polonius?” Mistaking him for a rustling rat, Hamlet has just dispatched the “intruding fool” Polonius—who was hiding behind a curtain, spying on an argument between Hamlet and Gertrude. In this song, Hamlet evasively implies to Claudius: “Hey, Bud, you’re next,” a point which Claudius fails to fully recognize.

Michael calls to mind Adrian Belew or David Byrne in his vocal delivery and phrasing of Hamlet’s spiteful script. Rene’s restless keyboard plays against the fluid motion of Captein’s bass. Her syncopated rhythms (she additionally plays drums on this track) lend a jazz feel to parts of the performance.

The lovely, Beatles-like gem “Ophelia’s Song” comes to us from the conclusion of Act 4, Scene 5, where Ophelia, grief stricken at the death of her father Polonius and Hamlet’s headtrips, briefly wanders through an impassioned exchange between her brother Laertes and the new king Claudius. It is clear from her ravings that she has gone off the deep end. She manages to sing a couple of songs within the text of her short appearance, but the Jarmers choose instead another delightfully sweet and crazy expression of her grief.

Michael and Rene duet harmoniously over her dramatic piano, orchestral string passages in the chorus and melotronish flutes in the second verse; moving toward a heart rending bridge at the end: “There’s fennel for you, and columbines—There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me.”

Captein adds mournful arco double bass to Rene’s bounding piano Tchaikovskian chordal leaps in “Denmark’s a Prison.” The narrative digresses to Act 2, Scene2 and an interaction between Hamlet and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern about what a ditch Hamlet thinks Denmark to be. It must be said that Hamlet maintains a pretty sour attitude throughout. The guy’s got a real chip on his shoulder. Personally, I think he’s bipolar.

The final number of the first act (Side One) of HCE’s play, “The Insult Song,” comes to us via A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Lysander launches a verbal assault against Hermia within the confused love quadrangle that serves as the plot for Shakespeare’s romp. The Bard is somewhat renowned for the remarkable versatility he displays in crafting an affront and here we find a fine collection culled from Act 3, Scene 2: “Hang off, thy cat, thou burr! Out tawny tartar. Out loathed medicine. O hated potion, hence. Canker blossom. Thou painted maypole.” Nothing but the hits!

The pretty ballad “Starve Our Sight” derives from Act 1, Scene 1 of A Midsummer Night’s Dream with Hermia providing the chorus, while her BFF Helena contributes the words for the verses. Rene’s moody piano arpeggios and Captein’s slippery double bass accent the complexly gorgeous vocal harmonies between Rene and Michael in the chorus. “We must starve our sight/From lovers’ food till morrow deep midnight.”

“The Course of True Love” and “Reason and Love,” also with roots in the first act of A Midsummer Night’s Dream venture from the script with additional insights inserted by HCE. “What Fools These Mortals Be” is very short, just the nugget of an observation from Puck to his fairy boss Oberon: “Shall we their fond pageant see?/Lord, what fools these mortals be!”

Extracted from discourse between Romeo and Mercutio in the first act of Romeo and Juliet, “Children of an Idle Brain” is the latter’s extended depiction of the world of Queen Mab, “the fairies’ midwife.” Michael gives an insightful reading, not exactly singing over the musical backdrop, but certainly in time with it—which emphasizes the rhythm in Shakespeare’s language, made real by our young actor’s way with those words.

Rene and Michael portray Juliet and Romeo in the touching call and response duet “Of Pilgrims and Saints,” taken from an incredibly romantic interlude near the end of Scene 1. In this instance, Shakespeare provides luscious rhyming poetry for lyrics, which the pair engage with obvious love and understanding (for the language—and the subject matter). The second half of this piece is an extended solo. While Captein pops a funk jazz informed bassline over a tumbling waltz, Al Torres returns for a wondrous trombone hiatus that hovers over the song like the cloud hanging over the young lovers’ doomed romance.

“A Plague” finds Romeo and Mercutio at the other end of their friendship in Act 3, Scene 1 of Romeo and Juliet. Mercutio has been stabbed on a cheap shot from Tybalt, a member of the Capulet Gang, the Montague Boys’ arch-enemies (except for Romeo and his thing with Juliet, of course). Rene vocally portrays the dying lad, who was friend to both of the feuding families, among his final words a familiar curse. “I am peppered, I warrant, for this world/A plague on both your houses!”

Rene’s solemn Lennon imagined electric piano delineations serve as Mercutio’s waning pulse, Glide’s bass a fading consciousness. Michael’s vocal at the chorus again calls to mind Brandon Flowers, sailing on a sea of troubled strings.

The brambled ramble of “Opposed Kings” finds Friar Laurence extolling the many virtues of the various plants, potions and philters at his behest, the bounty which mother earth provides her creatures. One of those elixirs will put Juliet in a state resembling death, convincingly enough that Romeo will then kill himself over it, so that when Juliet eventually awakens to find him dead, kills herself for real—because that’s just what lovestruck youngsters do.

A Radiohead disposition invests the musical atmosphere. Over a brittle electronic drumbeat, and Rene’s thick electric piano sound, Michael’s muttered tenor could pass as relative to that of Thom Yorke singing: “Within the infant rind of this small flower/Poison hath residence and medicine power/For this, being smelt, with that part cheers each part/Being tasted, stays all senses with the heart.”

This is such an ambitious album. Deep. It assumes upfront that the typical denizen of Portlandia might have some fleeting whit of an acquaintance with the playwright Shakespeare. Certainly, it should go without saying, the audience is greatly narrowed by the subject matter. But that is precisely why the Jarmers and Here Comes Everybody are the perfect heralds. Their words and music, their productions have always been difficult and intelligent.

This album is no great leap for them, but for the fact that the pair are forced to work with language that is over four hundred years old. And while Shakespeare’s use of the English language could not be considered contemporary, exactly, his command of human nature and the machinations we trivial beings contrive is no less accurate nor insightful all these four centuries later. And though his voice may be quaintly unmodern to our sophisticated ears, it is no less astute nor intuitive—nor rich with musical poetry —after all this time.

Through the course of this album, you can see the manic desperation of Robin Williams’ Hamlet foretold. The state of our nation, our world? “Denmark’s a Prison.” Can we not find echoes of the stupid deadly territorial skirmish between Tybalt and Mercutio rampant in the Arab world? And can we not see the enduring Romeo and Juliet like tragic aspects in the love between Kanye and Kim?

There are several songs that stick in the mind here. “The Play’s the Thing” stands out. “Ophelia’s Song” is two and a half minutes of pure pop pleasure. The haunting quality of “What a Piece of Work” remains imprinted on the psyche. “Song of Indecision” is a fast paced piece with a memorable chorus and a mouthful of bon mots.

Yes, the appeal of this album will be limited. That seems almost certain. But HCE knew that going in. And, given those limitations, the band produce superlative music to support timeless themes incomparably expressed.

The lesson to be learned from this two-act aural play is simple. Nothing much has changed about the human condition in the twenty generations since the ideas contained within were first presented to the public. Humans are screwed up and inscrutable. In the history of the English language, no one has illustrated that fact better than William Shakespeare. And Here Comes Everybody do a remarkable job of lending 21st century musical color to the presentation.