It seems like every century some composer decides he wants to take a crack at the solar system as artistic inspiration. Over the years this has gotten successively more difficult to create. In 1916 when Gustav Holst completed his orchestral suite, The Planets, Pluto hadn’t even been discovered yet. So his view of our little corner of the universe was decidedly incomplete and a tad bit smaller than our more enlightened satellitelian digital vantage point of today. In the past 90 years or so, Pluto has undergone the indignation of being batted about like a cosmic badminton birdie. Today it’s a planet, tomorrow maybe not. Actually, today it’s not a planet (I don’t think). However that is the topic of another story.

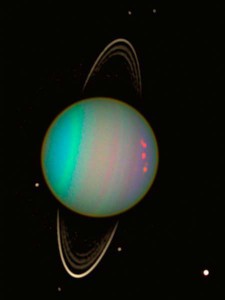

Holst crafted his planetary vision from an astrological standpoint, most likely owing to the fact that astronomy hadn’t really changed a whole lot in the preceding three hundred years since Galileo. Certainly William Hershel (a composer himself whose interest in mathematics actually led him to astronomy from music) livened things up at the beginning of the 19th century spotting Uranus and its two largest moons, Titania and Oberon—he had a thing for Shakespeare. But that was about it until 1930 when the new generation of telescopes allowed young Clyde Tombaugh to confirm “Planet X” at the Lowell Observatory in Kansas.

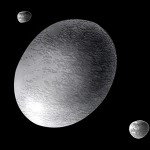

After a big contest it was decided that Pluto was its name-o. Now, after like twenty-five years spent searching for the damn thing throughout the early 1900’s, the International Astronomy Union has determined that Pluto should be demoted to the status of “dwarf-planet,” as if it were some asteroid like Ceres or Eris (granted, Eris is slightly larger than Pluto and even farther out there—but hey—maybe Eris should be a planet too! No, no, no. The IAU has its rules, even though they shift polarity every so often). There may be extreme pressure from the astrology lobby. Who can say?

So it’s hard to guess if Holst would have made a run at today’s solar system. Hell, at first he didn’t even name The Planets, The Planets. That didn’t come until late in the game. At first the suite was called Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra and referred not at all to the planets in play but only to their astrological presentations. Strange how these things evolve.

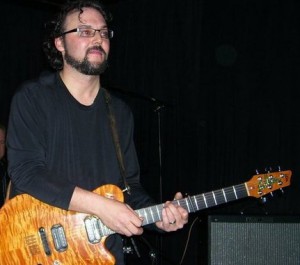

That brings us to Carlos Severe Marcelin. Carlos has been playing around our happy little mizzle-stop for the better part of twenty years. In the ‘90s he was lead guitarist for intellirockers, Silkenseed. Then, in the early Oughts he married fortunes with Sally Tomato, whose eponymously named band has been the source for a lot of strangely inimitable artiness over the years—Carlos responsible for a great deal of it. As a guitarist especially, but also as a controller of keyboards, Carlos has consolidated his considerable talents for the formidable task at hand.

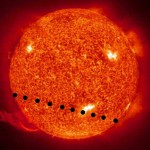

Carlos wrote “Earth” about ten years ago, as a stand-alone piece. It’s pretty obvious that most of us don’t think of Earth as a planet necessarily. It’s simply the only place we know. It’s just here. Planets are out there, out yonder. Look, there’s Venus in transit across the sun! Carlos had always admired Holst’s attempt at the subject. About three years ago, he started to launch various pieces into orbit. And from there things seemed to slowly fall in line. Voila. A concept album was born.

Thus Carlos created the planets and the firmament. But he didn’t do it completely alone (although he probably could have). He is joined in places by Ms. Tomato herself (as well as by a few other special guests). And longtime Sally Tomato drummer Eric Flint dispenses his usual spot-on sonic rocketry. But even by Tomato standards, this project is pretty impressive. In this configuration they call themselves Sally Tomato’s Pidgin. I don’t know why.

Though he professes not much familiarity with the genre (and at age forty he is too young to have been around for the original manifestations) of prog, Marcelin’s work has much in common with the artistic leaning of many well-known prog guitarists—including, especially, Andrew Latimer of Camel.

But one can hear stylistic similarities to the work of Robert Fripp (King Crimson), Martin Barre (Jethro Tull), David Gilmour (Pink Floyd), Robin Trower (Procol Harum and solo), John McLaughlin (Mahavishnu Orchestra), Steve Hackett (Genesis) and the two guys from Wishbone Ash (Andy Powell and Ted Turner).

Subsequent guitar heroes, such as Steve Morse (Dixie Dregs, Deep Purple), Steve Vai, Joe Satriani and Yngwie (of course) are also represented, it would seem, in one way or another. Carlos touches all the bases without being in the least bit imitative. He’s his own player.

In a display of acute astronomical awareness Carlos elects to begin our journey with the sun—old “Sol.” He could have, of course, followed Holst’s lead, which was astrologically Copernican in construct. But Carlos chose the more accepted course, unless you are among those yayhoos who believe that the earth is the center of the universe, and only six thousand years old, and man walked with the dinosaurs etc. If that is the case, you probably aren’t reading this masterpiece in the first place.

As might be expected, Sol is a rather bright and majestic object of real gravity in the musical construct. After a brief spoken prologue, intoned by Ms. Tomato, Carlos launches a fiery flare on guitar, evoking the prog-ish nature of Hot Rats era Zappa. Zappa would seem on the surface to be a touchstone influence—but that is hard to fully ascertain. I know for a fact that Carlos has never heard of Camel or Andrew Latimer. So there you go. In this context the theme is a soulful one delivered with great élan.

The next stop on our trek would be “Mercury.” Over Flint’s merciless polyrhythms, Carlos wields the sound of twin guitars (cue the Wishbone Ash reference), which soar in close precision. “Venus” is given a more exotic treatment—squishy guitar-synth driving the piece—possibly elementally derived from somewhere around Discipline era King Crimson. The brief “Luna” could easily have been composed from random frequencies generated by the cold, cold orb. Talk about trickle down!

A compendium of detritus is carefully inventoried (“Lepers, cartoons, and spiders. Men and women in intimate positions”) on “Earth.” Reverend Tony Hughes (Jesus Presley) delivers the benediction, sounding not unlike Fee Waybill of the Tubes: “Welcome to our not so humble abode in the cosmos—a flying chunk of dirt called Earth.” His observations are alternately punctuated by a chorus singing “We have it all” like an ad for an all-night convenience store. Reverend Hughes further elaborates. “It’s the human condition. Life after death: the ultimate mission. Black velvet paintings. Corn dogs and cotton candy. Mysterious scenes, novels, theater and TV in 3-D!”

The Reverend later returns, reporting “World of Now, twenty-four, three sixty-five. We all come back for a sigh or a laugh or something we lack. It’s the missing link. It’s hard core funky. Come on down and see the singular monkey.” From there the bugs come out and tell a tiny story of their own, while a disinterested voice injects, “Infinity is not a destination, it’s a state of mind.” Au revoir.

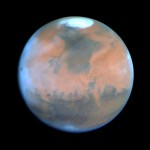

Concluding our tour of the four “inner planets” Marcelin’s portrayal of Mars as less martial in intensity and more reflective of rivers of red dust and perhaps a civilization long ago gone by. Dense keyboard pads and Flint’s precisely complex drumming underscore Carlos’ ornate pointillistic riffs and staccato lead figures. For some reason the Denny Dias/Jeff “Skunk Baxter twin-guitar solo intro of Steely Dan’s “Bodhisattva” comes to mind. You be the judge.

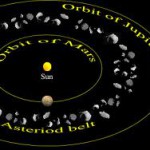

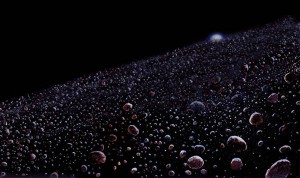

Next up: the asteroid belt. Honestly, I would have plotted the asteroid belt out farther, out around Neptune. But then, I have always thought Michigan lay east of Wisconsin and that Indiana and Iowa abutted, so what the hell do I know about geography, earthly or terrestrial? Anyway, the asteroid belt officially circuits between Mars and Jupiter. Deal with it.

As asteroids go, most of them are pretty damn flimsy and only of interest if we need to get one out of our way, or if there is some mineral or ice deposit worth going after. Profit motive, etc. But there are some (four) larger asteroids out there. They’re not that big—the largest being about a quarter the size of the moon (or of Pluto, for that matter). But Ceres and Pallas are two that often draw the most attention.

Ceres, the largest chunk in the asteroid belt—at six hundred miles across (Earth is about 8,000 miles in diameter)—was discovered in 1801 by Giuseppe Piazza and became designated as a planet not long after that. Assigning planet status was pretty much the only alternative to calling these bright objects in the sky comets or stars, until William Herschel coined the term (and concept) “asteroid.” And voila! Pallas was spotted in 1802 and was also given the planetary nod until the mid 1800s when astronomers cleared the deck—setting ground rules for planethood and the like. Always so formal, those sky guys.

All three brief “roid” sections interlock among the debris. Carlos introduces us first to “Pallas,” which can be found sort of in the middle of that spatial spread. The rest of the belt follows, en masse. Then “Ceres” concludes the excursion. All three pieces are quite regal and chipper in their own right, showcasing in spots Carlos’ more metalic persuasions.

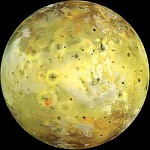

As we journey on toward Jupiter, we stop off at Io, the largest of the “Gallilean moons” and nearest to the giant gasbag; the fourth largest moon in our solar system (vying with our very own moon). The volcanic nature of that orb is given ethereal treatment: a ghostly instrument—e-bow? sax? synth? all three? interprets the subtle colors of the clouds of dust and ash.

The scope of “Jupiter” befits the massive planet known since antiquity. A giant red spot of distorted guitar rumble lumbers across the sparse atmosphere of helium and hydrogen. It’s a big body with no density. Ephemeral. Somewhere past mid-point a whizzy fizzy synth comes in to effervesce the scene, before resolving into a pensive mist, which recalls Mozart’s “Jupiter” Symphony No. 41.

Onward we fly toward “Titan,” the largest of Saturn’s fifty-three known moons. It’s thought that life could possibly exist on Titan, speculation underscored by the stately dignity of Ray Woods’ keys on the short piece. Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s take on “Picture’s at an Exhibition” is reflected here.

Soaring intervals bound across “Saturn.” Endless guitar sustain (Ebow?) swirls and slides like a siren call, glissading from one note into the next. A second section chords its way through a little Pete Townshendish (circa Tommy) sort of endeavor.

Leaving Saturn we pass by another of his many moons, “Dione.” As a compositon, the short piece is rooted in a sound-collage derived from signals sent back by the Cassini spacecraft in 2007. Again Ray Woods adds subtle keyboard support.

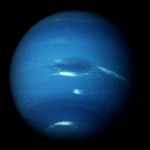

Slowly approaching the blue ice giant “Neptune,” we note in awe its windy surface. Carlos offers a pastoral depiction— indistinct as hydrogen and helium, sketching parameters upon a lighter than air acoustic guitar—evolving into a more orchestral pastiche augmented by synth strings.

Now, I know what you’re asking right about now. Why is Neptune portrayed here in planetary order before Uranus, when in actuality it lies beyond? I asked Carlos Marcelin this very question.

Some people think they switched about a billion years after the formation of our solar system. We have them in this primordial order on the album for thematic purposes—it was more fluid to have Neptune follow Jupiter before moving into the chaos and weirdness that is Uranus and Pluto.

In (what many will recognize as) a tremendous show of restraint, I will forgo my usual litany of Uranus jokes and just move along. Nothing to see here. Except Uranus.

With a short statement from our sponsors we fly swiftly by big, old, hard and chilly Oberon, the Uranian moon mentioned earlier, discovered by composer William Herschel. Uranus is atypical in that its axis is tilted sideways in relation to the sun. So its poles are where our equators are, and vice versa. Trying to work that out in your head will freeze it up pretty good.

Flint’s crazy, Phil Selway-influenced, cross-time drumming neatly sums up the arcane perturbations that comprise the planetry components of the coldest spot in all the solar system: Uranus. Carlos steers us with a strange, perky permutating theme. Overblown guitar skips merrily at times in the planet’s rarified atmosphere, before going all magisterial in the alternating passages. A schizophrenic piece, to be sure.

Approaching the outer reaches of our little corner of the galaxy, here comes poor, much-maligned Pluto. Pluto is a planet, a dwarf-planet, a plutoid, a plutino—or just a big ball of rock spinning around, way the hell out there, pick yer poison. Pluto’s orbit is so eccentric that sometimes it slides inside that of Neptune. I’m telling you: it’s a wacky galaxy. To capture Pluto’s mood (low self-esteem?) Carlos employs a music box scenario to back the other-worldly voice (text borrowed from the Society for the Preservation of Pluto as a Planet) that delineates the belief structure surrounding what used to be the ninth planet. It’s very confusing out there.

Pluto spins around in the Kuiper belt. The Kuiper belt is similar in construct to the asteroid belt, but it’s quite a bit more massive. And it’s located three times the distance from Earth as Pluto! Way the hell out there. The belt is about as far from the sun as it gets in our neighborhood. Most of the stuff floating around out there is either ice balls, or chunks of planet-like items that got smashed up once upon a time, long ago. There are a few more “dwarf planets” drifting around out there too.

One of those dwarves is called Haumea, a potato-shaped object with two irregular moons. Carlos gives “Haumea” an exotic voice—mystical. Yoko Ono-esque. Another of the dwarves is Eris, the final stop on our trip. Eris is bigger than Pluto, so for a long time there were astronomers who wanted to bring Eris into planethood. But that opened up the can of worms that eventually got Pluto kicked out of the club, so there you go.

Anyway, Eris (formerly known as Xena) is possibly involved in the upcoming Nibiru cataclysm, accepted as gospel by Doomsday fans everywhere, and occasionally linked to the whole Mayan calendar deal on December 21st of this year. So Eris has been presumed to be lurking out there, just waiting for the big day so it can come on in and pop earth a good shot. At least that explanation would account for why the Mayans decided to cut things off at that date. “Oh yeah, that mystery planet’s going to smash into earth on that day, so why bother?”

But back in 2003, just when the typical American sense of mindless, groundless fear generated by some unfounded rumor was about to ramp up, grumpy Mister E.C. Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, stepped in to quell the hysteria.

In particular, several threads of irrational thought have created an internet phantom, the secret planet Nibiru. It’s the bowling ball, and Earth is the pin. There is no such planet, though it is often equated with Eris, a plutoid orbiting safely and permanently beyond Pluto. Some insist, however, that a NASA conspiracy is in play and that Nibiru, looming in on the approach, can already be seen in broad daylight from the Southern Hemisphere. It was supposed to become visible from the Northern Hemisphere, too, by last May, but like a fickle blind date, it stood up those awaiting it.

Damn fickle planets of Doom. If you can’t count on them, who can you count on? For Carlos’ part, he decided to go Lost in Space with “Eris,” lots of actual loops of the original Class M-3 Model B9 exclaiming. “Danger, danger, Will Robinson. Warning, warning.” Idiosyncratic guitar stylings, reminiscent of Adrian Belew, color the piece.

As ambitious as this project is, Carlos Severe Marcelin can only go outward if he wishes to continue along these thematic lines. The Milky Way. Norma and Outer Arm. Perseus and Cygna. Although, one would suppose, he could go inward and explore theoretical physics or cells, molecules and atoms and all the sub-atomic particles. Quarks and Bosons and Hadrons. Oh my!

Mention must be made of engineer Diamond Dave Friedlander’s contribution to the sonic grandeur here. Clean and pristine, his mix is as uncluttered as space itself. The perfect complement—truly spatially open and expansive.

Planets is certainly grand in scope. Big. Real big! Carlos combines the familiar with the futuristic in uncommon ways, approaching this mission with musical exuberance and lucidity, sounding as the culmination of forty years of progressive rock guitar exposition. He isn’t showy. But he is consistently diverse and ineluctably imaginative in embroidering each of the twenty tracks with a distinctive design, while maintaining a cohesive conceptual aggregate. Not easily done.

But he does it almost effortlessly. The fluid sureness of his execution, supplemented by Eric Flint’s always compelling drum accompaniment, makes for a robustly stellar experience—difficult to compare in a rock context. Far more comprehensive than Gustav Holst’s treatment of the subject, Carlos Marcelin finds the music in the spheres that astronomer/composers such as Herschel always sought. This is a worthy effort toward that aim.