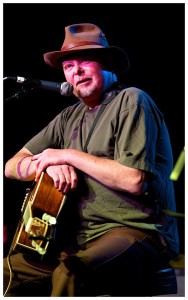

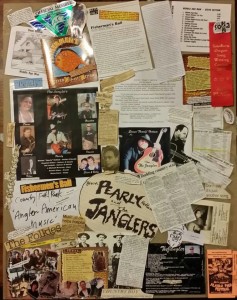

Richard Lloyd’s place in the annals of rock music is secure. For over forty years he has proven himself to be one of the most versatile and knowledgeable guitarists in the business—with a career that begins with the founding of the new music scene in New York in the early-70s, extending through to the present, where he is a sagacious purveyor of a very highly refined craft.

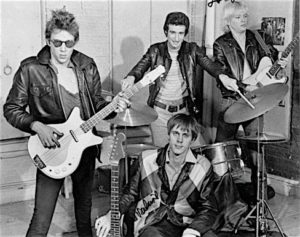

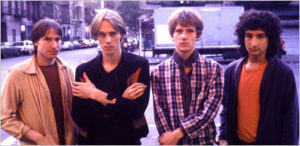

Along with Richard Meyers (bassist Richard Hell) and drummer Billy Ficca, Richard Lloyd and his partner, guitarist Tom Miller (Verlaine), formed the band Television in 1973. Even more importantly for their own success, and that of countless other bands, the fledgling Television were instrumental in helping bar owner Hilly Kristal convert his country/blues dive bar into the quintessential punk/new wave dive bar: CBGB. The prototype. The heights (and depths) to which all punk/new wave dive bars aspired.

Television is renowned to have constructed the actual stage in the club as a demonstration of their solidarity. Hilly Kristal himself proclaimed that he thought Television’s first show at the revitalized club in March of 1974 was the “beginning of new wave.” To be sure, innumerable Rock and Roll Hall of Fame bands found their footing on that rickety CBGB stage, and made their subsequent fortunes from the incredible creativity that was spawned there at that magical time.

With Hell replaced by Fred Smith of Blondie, Television broke out nationally in 1977, via the release of their debut album, Marquee Moon, on the Elektra label—an album that to this day is regarded as one of the most seminal records in all of rock music history. In support of Marquee Moon and their follow up, Adventure, Television actually played the Earth Tavern in Portland in July 1978, with a molten set (a bootleg recording of which is available out there if you want to track it down. It’s worth the effort believe me!) Check out this version of the song “Marquee Moon” taken from that performance.

What made Television special, then as well as now, was their unusual twin-guitar attack, which featured complex interplay between Lloyd and Verlaine. Television were always considered outside of “new wave,” not settling into any specific box—which made them far more difficult to market than some of their peers, such as Blondie, Ramones, Talking Heads and Patti Smith, etc. The band never quite found their niche. They essentially broke up by the end of 1978.

What made Television special, then as well as now, was their unusual twin-guitar attack, which featured complex interplay between Lloyd and Verlaine. Television were always considered outside of “new wave,” not settling into any specific box—which made them far more difficult to market than some of their peers, such as Blondie, Ramones, Talking Heads and Patti Smith, etc. The band never quite found their niche. They essentially broke up by the end of 1978.

Their brief existence in the spotlight and lack of a convenient musical pigeonhole did not prevent Television from being highly influential. The Cars owe much to Television. Cars Ben Orr and Ric Occasek both sing in a highly stylized manner very similar to Verlaine. And though far more a pop band, their presentation owes a great deal to Television’s audio prescience. More recently, the Strokes have proven on occasion that they have spent some time in the living room with the Television. It’s a sound. It’s a feel. It’s woven fabric. Sonic Kevlar.

Post Television, Richard proved himself to be a talented, if somewhat erratic, solo performer, releasing two influential records: Alchemy in 1979 and Field of Fire in 1985, and the little heralded Real Time in 1987, before entering an extended period of performance as a side musician. From 1991 through 1995 he sporadically alternated with the late Robert Quine, serving as lead guitarist, both on tour and in the studio, for Matthew Sweet. He contributed numerous fiery solos to Sweet’s two finest albums, Girlfriend in 1991 and 100% in 1995.

In 1992, Television reconvened for an eponymous third album that succinctly recaptured a sound the group had abandoned fifteen years earlier. The band infrequently played a few influential live concerts in the years that followed. Lloyd left Television, once and for all, in 2007

In 1992, Television reconvened for an eponymous third album that succinctly recaptured a sound the group had abandoned fifteen years earlier. The band infrequently played a few influential live concerts in the years that followed. Lloyd left Television, once and for all, in 2007

He released The Cover Doesn’t Matter in 2001. It’s not an album of covers, as one might expect from the title, but a collection of great original songs—clearly a distillation in many ways (the songs themselves and their arrangements) of the Sweet Experience. Fans of the aforementioned Matthew Sweet albums would find much to appreciate in The Cover Doesn’t Matter.

He released The Cover Doesn’t Matter in 2001. It’s not an album of covers, as one might expect from the title, but a collection of great original songs—clearly a distillation in many ways (the songs themselves and their arrangements) of the Sweet Experience. Fans of the aforementioned Matthew Sweet albums would find much to appreciate in The Cover Doesn’t Matter.

In 2003 Richard lent his NYC sensibilities to the Cleveland consciousness of Rocket From the Tombs, joining Cheetah Chrome (Dead Boys) and David Thomas (Pere Ubu) to explore anew the retrospectively precocious musings of the long deceased band founder Peter Laughner (also Pere Ubu—and an early admirer of Television, before his death in 1977), culminating in the release of Rocket Redux in 2004.

As with his previous solo album and Matthew Sweet, 2007’s The Radiant Monkey suggested Lloyd’s experiences with Television and Rocket From the Tombs: posing a tougher, more raw sound, while capturing some of the fire of his early solo career: the prickly quickness of his deft fretwork never far from the fore.

The Jamie Neverts Story, issued in 2009, is a tribute album directed toward two people who influenced Richard, as a guitarist, more than any others. One was his high school friend and fellow novice guitarist Velvert Turner, and the other was Jimi Hendrix. One thing that distinguished Velvert Turner from just about any other teenager in the world was the fact that he actually knew Jimi Hendrix, and visited him in his flat when he was in New York for a concert or for recording.

The Jamie Neverts Story, issued in 2009, is a tribute album directed toward two people who influenced Richard, as a guitarist, more than any others. One was his high school friend and fellow novice guitarist Velvert Turner, and the other was Jimi Hendrix. One thing that distinguished Velvert Turner from just about any other teenager in the world was the fact that he actually knew Jimi Hendrix, and visited him in his flat when he was in New York for a concert or for recording.

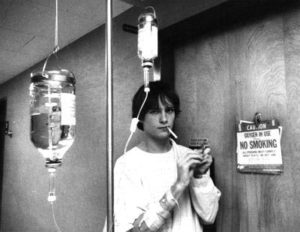

Velvert would receive a guitar tip or lesson from Jimi and run directly over to Richard’s house to show him what he’d just learned. Together, the two young men mastered many of Jimi’s unique early techniques. It was through Velvert that Richard met Jimi Hendrix and was afforded the opportunity join with Turner in the studio (presumably the Record Plant for the Electric Ladyland sessions) to listen to mixes with Jimi.

Jamie Neverts was a covert code-name the two concocted in order to hide the identity of their famous mentor from friends at school. Richard has distinguished himself as a spirited raconteur, and he spins this tale in one of his many online interviews. (Also not to be missed are his esoteric guitar lessons—the series entitled The Alchemical Guitar—presented by Guitar World magazine).

Velvert Turner released one lone album in 1972, a few years after Jimi died. And Velvert died in 2000, long away from the business of music by that time. But an audition of the guitar and vocal work on his only recording leaves no doubt as to the imprint Hendrix left upon him.

Likewise, it’s hard to tell where Richard Lloyd’s tribute to Hendrix begins on The Jamie Neverts Story (all ten numbers are faithful renditions of songs taken from Are You Experienced? and Axis: Bold as Love), and where the homage to his fellow acolyte begins, as their shared assimilation of the teachings of the master are not to be denied. They both learned their lessons very well.

Over the course of his career, Richard manifested those principles in myriad ways—perhaps the influence of Hendrix is not readily apparent in the twin guitar onslaught of Television. But then again their propensity for harmonic discord seems philosophically in accord with the master.

And since leaving Television, Richard Lloyd has spent the better part of forty years wandering the horizons of possibility his instrument offers. Moving from solo album to solo album, over the years, Richard has covered a lot of stylistic ground, seldom repeating himself. Every one of his solo albums has had an identity all its own. Each seems to acquire subtle features from the previous project.

And since leaving Television, Richard Lloyd has spent the better part of forty years wandering the horizons of possibility his instrument offers. Moving from solo album to solo album, over the years, Richard has covered a lot of stylistic ground, seldom repeating himself. Every one of his solo albums has had an identity all its own. Each seems to acquire subtle features from the previous project.

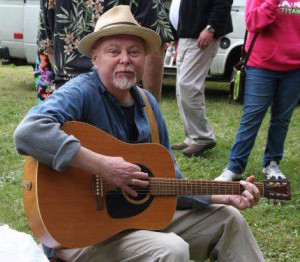

So there are intimations of The Cover Doesn’t Matter and The Radiant Monkey (and always the work of Hendrix) in Rosedale. Still, though much of this was recorded before the event, something in this album reflects Richard’s recent move from his long-time home in New York City to a rural setting outside of Chattanooga, Tennessee. There is a laid-back swampiness in the stylistic attitude displayed here. Even the name of the album suggests a rustic, burnished quality borne out by the music itself.

It’s a pastoral collection, a guitar record, pure and simple. But the Lloydian riffs are the same as ever, playing out against different contexts. More subdued. More laid-back, perhaps. Rootsy rock. Performed pretty much live in the studio with a minimum of overdubs, there are no supporting keyboards or background vocals, no sax solos. Just the basics. Drums, bass, vocals and guitar—maybe the occasional overdubbed guitar. But that’s it. No studio trickery. Simply the straight shit.

The brief, jagged riff that opens “Crystal Mountain” plumbs directly back to Television before resolving in a ballsy rocker with bluesy undertones. Richard plays all the instruments on this number, with crisp, whipsmart guitars decorating the periphery. There is a Joe Walsh-like quality to the vocals, bolstered by the general feel of the production.

Chris Frantz (Talking Heads) provides the beat on “The Word,” another rocker with big cajones. There are hints of Lou Reed in the vocals—as well as Steve Kilbey of The Church—but this song swaggers far too fast for the former to keep pace, and too forthrightly for the latter’s informal vocal gait. The guitars gear like a watchspring, each cog turning another wheel. The effect is as if the guitar methodology of Television had landed in some other completely different thematic space.

“I Want You” is a primitive piece of work, originally recorded to 4-track. It’s a slow soulful blues-fueled number, reminiscent of Otis Redding, Percy Sledge or Joe Tex, with a touch of Lennon lime squeezed in. Richard navigates a rich falsetto through the vocal changes, wringing raw pathos from the tortured lyric.

Billy Ficca takes over the drum chair for the next five songs. His longtime association with Lloyd, via their time together in Television and after, coats Richard’s instrumental vehicle like a thick coat of paint. “Everytime It Rains” is very Sweet-like in its composition. Ficca’s drums bridle the intense prance of Richard’s keen guitar phrasings. He pins the ears back on a fantastic solo to lead out the final forty-five seconds of the song, with Billy playing the role of Mitch Mitchell. Hot! Hot, hot!

Which jumpstarts the reptilian slither of the next cut, “Tasting Quicksand.” Into a crucible riff that alchemically fuses elements of The Heads’ “Life During Wartime” with the Nuge’s “Cat Scratch Fever,” are stirred Richard’s goosey, falsetto infused vocal—reminiscent of Jagger circa “Fool to Cry” in the verses. The gritty chorus furthers the Jagger feel, more in the direction of the “She’s So Cold” era.

“Murder Boogie” is imminently self-descriptive: a swampy, ZZ Top-ish shuffle that affords Richard room for lots of tasty fills and blade-sharp solos, over a nasty vocal of wicked intent. Ficca’s bold beat drives “The Real Girl,” a charming pastiche of Television’s angular dynamism buffed with a country sheen—as sung, alternately by Warren Zevon, David Byrne or Marshall Crenshaw.

The blustery rocker, “Easy,” is so familiar, it sounds as if it has always been in the rock music canon. It could have sprung from any era. Richard tosses out a few Hendrix infused runs in the solo sections and the song breezes by like a springtime love affair. Catchy. The hook sticks in the mind like gum to a shoe.

The final two tracks feature support from musicians culled from the Chattanooga scene, and were recorded after Richard’s move to Tennessee last winter. It’s clear from the start of “Devil’s Design” that drummer Jeff Bonebill is up to the task of replacing the formidable Billy Ficca. And the addition of Terry Clouse on bass rounds out the sound as well, freeing Mister Lloyd to turn out low-slung sidewinder licks, and brash, slashing chord punctuations. The song could be the work of the Pixies—with some guy of Richard Lloyd’s magnitude playing lead guitar. Vocally, it’s a cross between the frankness of Black Francis and the reediness of Lou.

Richard Lloyd is not availed of the greatest singing voice in the world, but he manages to take it a lot of places. He gets his point across via rough hewn lyrics: sometimes course, sometimes dirty and gritty, sometimes smooth and resonant. Still, the centerpiece of this album is the unique guitar work.

Every riff, each run, presented across the span of the entire album is dead on the money. Clarion flashes of clarity, and an acupuncture precision of attack differentiate Lloyd from the typical guitarist. He has nothing to prove to anyone.

Every riff, each run, presented across the span of the entire album is dead on the money. Clarion flashes of clarity, and an acupuncture precision of attack differentiate Lloyd from the typical guitarist. He has nothing to prove to anyone.

This isn’t a great album. He hasn’t recorded his great album yet. But this album is solid from start to finish and quite enjoyable for its diversity and flair, and certainly worthy of his legend.

June 2016