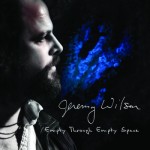

No Cities to Love

No Cities to Love

Sub Pop Records

In my most recent review—of Monica Nelson and the Highgates—I mentioned that Kathleen Hanna was inspired to form Bikini Kill after seeing Monica perform with the Obituaries in Olympia back in the late ‘80s. It was Kathleen Hanna and Bikini Kill, and other early riot grrl bands of the early ‘90s that first inspired Evergreen College students Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein to take up guitars and engage the fray.

For Brownstein it was with Excuse 17. For Tucker it was in Heavens to Betsy. In those bands the young women first honed their chops. So when they came together at the end of 1993 to form Sleater-Kinney, their punk ethos was fully formed. Accompanied by Aussie drummer Lora (Laura) Macfarlane, the pair traveled Down Under in 1994, to celebrate Corin’s college graduation. It was while they were in Australia that they recorded their eponymously titled debut album, released in 1995.

In 1997, drummer extraordinaire, Janet Weiss joined the team before they began work upon the band’s third release, the seminal Dig Me Out— an album which cemented for Sleater-Kinney a national presence with fans and critics alike. Over the next eight years, the succeeding four albums only found the band growing in popularity and prestige. Taking advantage of their newfound visibility, they became spokeswomen for LGBT, feminist and array of humanitarian causes.

The members of Sleater Kinney have always shared a spirit of adventure and have individually formed or played with many other bands over the years. Hell, Sleater-Kinney began as a side project. Corin formed Cadallaca with Sarah Dougher in 1997 and continues that concern up to present, though on a back burner for several years. Carrie recorded with Mary Timony of Helium an EP in 1999 under the name the Spells. Janet’s services have always been in constant high demand for side projects. One of those stints was in 2000 with the Go Betweens. In the late ‘90s she participated on three albums with her ex-husband Sam Coomes and their band Quasi.

Then, when Sleater-Kinney “broke up” in 2006, the three women went their separate ways. Weiss continued to sit in with any number of highly visible acts, including Connor Oberst and Bright Eyes, and Stephen Malkmus and the Jicks, while maintaining her seat in Quasi, and later teaming with Carrie in 2010 to form Wild Flag with Mary Timony and Rebecca Cole. Tucker took the time off to be a mother to her son, who is going to be fifteen this year. In 2010 she released the low-key 1,000 Years, an album she herself called her “middle-aged mom record.” She bounced back in 2012 with the release of Kill My Blues, which was a record much nearer to what a fan would expect to hear from her, and far closer to the vocalist we find here.

Carrie Brownstein’s meteoric post-Sleater-Kinney rise has been the most visible, as she has been pretty much incessantly everywhere in one form of media or another since she left her thirty-month tenure at NPR in 2010. That was the year she formed Wild Flag. She’s always been attracted to acting and had participated in a variety of independent film projects before she began teaming up with Fred Armisen in 2005 in a comedy duo called Thunder Ant. They made a variety of video shorts. That eventually led, of course, to Portlandia, which has ruined permanently our city for all true natives. For that I hold Armisen solely responsible, as I have long contended that Carrie can do no wrong—and I’m not about to change that opinion at this late date. But just the same: No Cities to Love, indeed!

After nearly nine years out of the pop music picture, it’s not entirely clear what prompted this reunion. Yes, it is the twentieth anniversary of the release of their first album. And perhaps they wish to view the world from the other end of that telescope, now with the adultly jaundiced eyes of middle age. No longer riot grrls, angry homemakers, perhaps.

There are other explanations, too, perhaps best mapped out by Tucker in the first song, “Price Tag.” “I was lured by the devil/I was lured by the cause/I was lured by the fear/That all we had was lost/I was blind by the money/I was numb from the greed/I’ll take God when I’m ready/I’ll choose sin till I leave.” Whatever the case, this is not the band that rolled out Sleater-Kinney in 1995. But, then again, that estimation is nothing new.

There are other explanations, too, perhaps best mapped out by Tucker in the first song, “Price Tag.” “I was lured by the devil/I was lured by the cause/I was lured by the fear/That all we had was lost/I was blind by the money/I was numb from the greed/I’ll take God when I’m ready/I’ll choose sin till I leave.” Whatever the case, this is not the band that rolled out Sleater-Kinney in 1995. But, then again, that estimation is nothing new.

Fans were bitching fifteen years ago that trio had lost their punk bona fides, that The Hot Rock wasn’t edgy enough in 1999, so my own misgivings about certain aspects of this project are not without historical precedent—though the bulk of the mushiness can be attributed to John Goodmanson’s production choices. The band’s rawness has been deeply seared to a dry char. There’s still smoky, meaty flavor there, but all the juice has been cooked out. In this particular instance, the overcooked piece of meat is served smothered in mushrooms and gravy.

Remnant shards of the jagged riffs Brownstein broke off on The Woods (and with Wild Flag) have all been polished smooth in the mix, doubled and re-doubled. Fans acquired through David Fridman’s more stark production with The Woods, might find the return of Goodmanson’s thicker, denser mix (as last heard on One Beat in 2002) somewhat disconcerting. Perhaps more so, because Goodmanson seems to have procured a number of new effects devices and a replenished penchant for multi-tracking.

Fifty years ago communication theorist Marshall McLuhan introduced the idea that the medium is the message (also that the “medium is the massage”). That point is proven here. To a T. Gone are the unabashed anger and fury, replaced by effects and caution. It’s a good sounding record. You’ll marvel at the production. But at a certain point the actual music is overwhelmed by that production, to the point where one must hack through a jungle of sonic distractions just to get to the clearing where the real song is camped.

This is the fifth crack Goodmanson has had at producing a Sleater-Kinney album since his first opportunity with Call the Doctor back in 1996. With each succeeding album his imprint on the finished product has become more evident, to the point where the band really can’t recreate the studio wall of sound on stage. Nor should they. Check out the studio version of “A New Wave” and weigh it against their performance of the song on a recent David Letterman show.

I could not begin to appreciate this album until I stopped trying to hear it as a recording by Sleater-Kinney. It’s not. It’s a work created by three women who were highly influenced by Sleater-Kinney back in the day, and they have many things in common with that band. But this isn’t a Sleater-Kinney album. It’s something else. And once I started to listen to it in that light, I was finally able to start enjoying it for what it is: a really well put together record.

Carrie leads off “Price Tag” with a characteristically gnarled guitar riff: richocheting gunfire, wanged out to the max in either ear (doubled and delayed just so), moving toward a guitar synth (of all things) sound: Belewery, Frippery, Carlos Alomar. Corin delivers a rather restrained vocal through the verses, stepping it up in the back half somewhat. But by the chorus, she’s in a full-on holler rage and clear the decks! Whereas Corin used to sound like a kid yelling at her mom, she now sounds like a mom yelling at her kid. But either way, I wouldn’t want her yelling at me. As I have observed before, she is the female Zach de la Rocha and no one else sounds like her.

The lyric addresses the everyday mundanity of the typical, working class American and the price we pay to purchase the things we love, a price appraised by our own decline as a culture. “We love our bargains/We love the prices so low/With the good jobs gone/It’s gonna be raw.” Janet pounds home the bridge and final chorus of the song with punchy ferocity—kick and toms thumping like a herd of charging horses. But then a lot of needless sonic bullshit goes on to distract the listener down the homestretch. The women still have plenty of power all their own, it seems strange that such pyrotechnic clutter was deemed necessary. But there it is.

There is some stunning ensemble work on “Fangless,” with Carrie’s fiery riff dancing against Corin’s mock-bass lines, over Janet’s unrelenting drums. But the production wangery on the periphery—apparent buzzing synth dribbles—is so distracting it becomes impossible to actually concentrate on the track. Maybe it’s me and my ADD, but I don’t think so. Corin belts out the verses and Carrie carries the choruses, a tale of the fallen mighty. Dig it out, if you can.

Goodmanson is at it again with the quintessential S-K anthem, “Surface Envy.” He feels compelled, for some reason, to jack up the side-fill guitar flourishes, to the extent that they distract from Corin’s smoldering vocal. “Throw me a rope, get me a line/I haven’t seen daylight in what must be days.” There’s certainly a lot of great playing going on here—most of it pinched between twinned wheels of whirring musical information lodged at the exteriors of the stereo field. Maybe there’s so much great playing that Goodmanson couldn’t decide which parts to include or where. But those parts could have been parsed out over the course of the entire song, instead of competing with themselves for attention.

The performance, especially the muscular interplay going on in the “center” channel, is quite powerful—like 21st Century Go-Gos on steroids, they got the beat! Shit, yeah! “We win, we lose/Only together do we break the rules.” This song is going to end up on every cardio workout mix in the nation, no doubt. Just the same, there are occasions when one might prefer to hear the band simply stripped down to the essentials found in the middle of the mayhem. That band sounds like Sleater-Kinney!

Finally some space, some room to breathe in the title track. Carrie’s angular guitar figure scrapes majestically against Corin’s churning “bass” lines. And Carrie takes the insouciant vocal reins here, distinctly calling to mind Debora Iyall of the ‘80s band Romeo Void (think “Myself to Myself”), with detached aplomb. “Atomic tourists/A life in search of power/I found my test site/I made a ritual of emptiness.” Now that’s anomie!

The curious chorus is bound to rouse the rabble, with gang vocals that sound like a mob armed with pitchforks and torches—though the precise message, “It’s not the cities, it’s the weather we love,” is a difficult mantra to contemplate, and may overstate the message to a certain degree. The pretty bridge is very well built, but the conclusion: “I’ve grown afraid of everything I love,” doesn’t seem to fit contextually to the rest of the obviously obscure lyric. Maybe this is a song about climate change and I’m just not getting it. The cut sounds real good. Urgent. It’s just not entirely clear what all the urgency is about. The weather?

“A New Wave” is chock full of so much frosting, it’s hard to find the cake—perhaps an audition for John Goodmanson’s next project, but a real mess all the same. Weiss’ stuttering drums lead into another of Carrie’s sterling twisted guitar figures. Goodmanson’s penchant for splitting the lead guitar, either electronically or by doubling, is in especial evidence here. Personally, I think the idea of recording a three-piece band freaks him out.

Bordering on incoherent, the lyrics hold together long enough to get to a catchy chorus: “No one here is taking notice/No outline will ever hold us/It’s not a new wave, it’s just you and me,” which would be catchier still if it was a turnaround for an even more attractive hook. Just the same, it’s a memorable number that is bound to have emotional currency for someone.

All desperately grappling for attention in the chaotic mix of “No Anthems,” writhing coils of Page-like (think “Dancing Days” from Houses of the Holy) cobra licks strike venomously against blown out synth bass and curious “ukulele” applications. Even Corin of the muscular shout is interred in the mix, wherein the chorus is perhaps more self-referential than even she might be willing to acknowledge. “I’m not the anthem, I once was an anthem/That sang the song of me/But now there are no anthems/All I can hear is the echo and the ring.”

I think she’s wrong about the first part. There are anthems galore on this album, even if most of them have a somewhat cumulonimbus mission statement. But I’m with her on the second part, because all I too can hear is echo and ring: cho-ring, cho-ring, cr-ing, cr-ing, cr-ing—echoing and ringing through the fog.

“Gimme Love” is a bit of an outlier on this album. And, as such, it hardly sounds like Sleater-Kinney at all. But for the relentless piercing clarion of Corin’s bullhorn voice, you would not recognize it as such. Built on a tireless gyre of triplets (as with the title itself), no one seems to have any idea what to do with the song. Carrie gives it a try, grinding out gritty bone meal guitar. But Janet sounds as if completely cornered. And, when his services could actually be put to some practical use, Goodmanson backs away and wipes his hands of it.

Janet delivers the Bonzo in the intro to “Bury Our Friends,” with a cut time salvo worthy of the master. Because she plays a vintage four-piece Ludwig kit, Janet can often sound like Ringo, or a stripped down Bonham. Carrie’s guitar figure sounds welded to a Franz Ferdinand frame. But soon we are whisked into a waltz in the verses; the guitar weaves and stutters, as Corin and Carrie trade vocals.

They come together for the powerful chorus, perhaps the fiercest and most focused statement presented in the set. “Exhume our idols and bury our friends/We’re wild and weary but we won’t give in/We’re sick with worry/These nervous days/We live on dread in our own gilded cage.” That’s a message that comes across loud and clear, despite the goop Goodmanson ladles on, and it’s another among several cuts with real radio-friendly memorability, though mostly unintelligible.

“Hey Darling” sounds like a real, honest-to-goodness pop song of indeterminate origin: ‘60s girl group transported to the present, perhaps—not necessarily S-K—until the chorus when Corin cuts through the bluster with characteristic chainsaw amplitude and we remember where we are. It’s not unusual on this album for Sleater-Kinney to not sound like themselves, but here they don’t really even sound like the band who recorded the rest of the material. This is such a weird album!

For the final track, the apocalyptic “Fade,” Carrie knocks off a pretty decent facsimile of Slash’s prickly intro to Guns ‘n’ Roses’ “Sweet Child of Mine.” From there the opus launches into a mini rock opera of epic proportions, worthy of Kate Bush or Tori Amos in their most ambitious moments.

There are at least four separate sections to the piece, possibly more, the most gripping of which is the chorus: “All of the roles that we played/Hit your mark, push the walls, stretch the stage/Oh, what a price that we paid/My dearest nightmare, my conscience, the end.” Talk about dark! The melody here sounds like an extension of Kate Bush’s “All the Love” from The Dreaming.

Without question, this is the most puzzling, the most complexly perplexing record I have ever chosen to review. It is of a breed like no other, perhaps a portent of the future, the sound of things to come. Or maybe the final sayonara from a band that aren’t entirely sure they should have regrouped at all in the first place, ten years after dissolution. Because the report from the trenches they populate crackles with midlife crisis and self-conscious second-guessing.

Without question, this is the most puzzling, the most complexly perplexing record I have ever chosen to review. It is of a breed like no other, perhaps a portent of the future, the sound of things to come. Or maybe the final sayonara from a band that aren’t entirely sure they should have regrouped at all in the first place, ten years after dissolution. Because the report from the trenches they populate crackles with midlife crisis and self-conscious second-guessing.

Beyond that, however, is the bald fact that this is the first album I have ever reviewed where the band (and still a very good band) was subservient to the producer. I have been wracking my mind trying to recall an occasion in rock music history (there are probably many, but none come to mind since the days of Phil Spector) where such a thing has happened. Much of pop music released today is dictated by the tastes of the producer, rather than the artist. There are countless examples of that.

But in the rock arena it simply isn’t done. George Martin was integral to the Beatles sound, but his production choices didn’t dictate the final sonic outcome, even when his involvement in a track was to the extreme. In the ‘80s everyone went with Steve Lilywhite. He would put his mark on the recordings he produced, no doubt. But he did not commandeer them. Even Brian Eno couldn’t do what John Goodmanson has managed to do here. He has taken a band with incredible amounts of raw energy and a readily identifiable sound and managed to render it nearly identifiable. Close the offramp, it’s Sleater-Goodmanson now.

For what it is, this is a good album. The songs have catchy hooks and memorable choruses galore. But I’ll be damned if I can find the band in all of this. Maybe that was the their intent all along, but if so, then that’s a pretty cynical choice and sounds like a sellout. Maybe the members’ musical tastes have changed so radically in a decade that it makes sense to drench their “message” in barrels of aural treacle. But I don’t get it.

Each of these compositions could have stood on its own, captured with just the band performing beneath a single mic. The component parts are in place. All the members seem to have improved or refined their individual styles and techniques. The songs may be impenetrable (the lyrics have been called “inscrutable” elsewhere. Inscutable, hell. A lot of the lyrics here sound pasted together via the William Burroughs cut-up technique), but all but two or three are certifiable hits—that you’ll recognize the moment you hear them on the radio (or in the stream).

Each of these compositions could have stood on its own, captured with just the band performing beneath a single mic. The component parts are in place. All the members seem to have improved or refined their individual styles and techniques. The songs may be impenetrable (the lyrics have been called “inscrutable” elsewhere. Inscutable, hell. A lot of the lyrics here sound pasted together via the William Burroughs cut-up technique), but all but two or three are certifiable hits—that you’ll recognize the moment you hear them on the radio (or in the stream).

The only problem is: you won’t recognize who’s performing them. For a band that is celebrating its golden anniversary this year one would think they would emphasize the strengths that brought them to this point, rather than try to bury them. But buried they are. This recording is gaudily ornate, needlessly dense, and ignores its own virtues. Gone are the riot grrls. Here come the acquiescent old gals.

January 2015