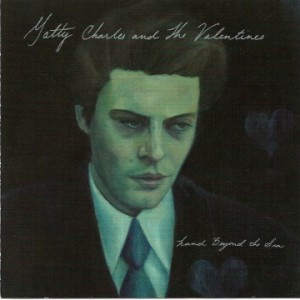

A Man Walks Into a Bar Vol. 1

A Man Walks Into a Bar Vol. 1

Sack of Hits Records

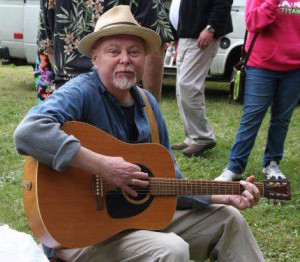

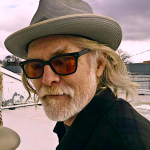

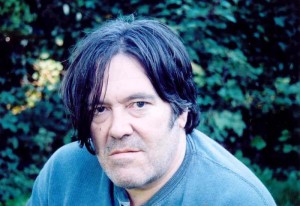

There is no one else quite like Ed Haynes in all of Portland. That’s a mighty tall contention, but after all the time I have spent listening to local music acts, I can unequivocally state that I’ve never heard anyone quite like him. He’s a curious musical anomaly, who stands apart from trends, while serving as the terminus of a long tradition.

The practice may go back further (Woody Guthrie?), but for our purposes let’s say it began with Tom Lehrer. Ed Haynes is a fan. Lehrer played the hip clubs in the ‘50s and ‘60s, writing and performing bitingly acerbic satirical songs with insights into events of the day, accompanying himself on the piano.

His first album was recorded in 1953 for $15. Self-promoted, the record slowly became a national underground sensation. Over time, with a couple of better recorded follow-up releases he became known as a known source for social commentary. Eventually, Lehrer went on to write ten songs for PBS’ The Electric Company, a children’ program that preceded Sesame Street.

The folk movement of the late 50s and early 60s ushered in a new breed of insightful bards, beginning with the likes of the Limeliters—who brought an extra level of innuendo to the traditional folk music they played. The Smothers Brothers soon followed suit. Johnny Horton, Jimmy Dean and Ray Stevens arrived on the airwaves with mainstream novelty appeal, followed shortly thereafter by Roger Miller. Then songwriters such as Dylan and Phil Ochs gave the lineage new perspective.

And from that core sprung an array of arcane storytellers such as Townes Van Zandt, Arlo Guthrie, Randy Newman, Jim Stafford, Jim Croce, Harry Chapin, John Prine, Tom Waits and Jimmy Buffett, etc. But, since the mid 70s, that well seems to have run dry. Careers have been maintained over the intervening decades. But there’s been no new blood.

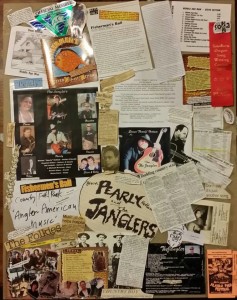

That is, until Ed Haynes showed up on the scene. Ed is the step-child culmination of all that went before him. He first appeared in the late ‘80s to take up the mantle of his predecessors. But it just so happened that, with metal, punk and new wave (and eventually grunge) at the fore, the musical landscape had shifted like quicksand beneath his feet and he could find no real purchase or center of gravity for his uniquely idiosyncratic compositions.

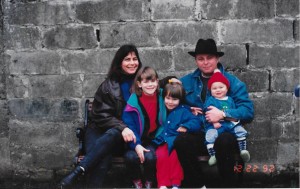

Ed was born just outside of the DC beltway in Springfield, Virginia the year the Beatles landed stateside. He moved with his family to the Bay area when he was fourteen, just around the time he first started playing guitar and writing songs.

Ten years later he released his first album, Ed Haynes Sings Ed Haynes (an album long out of print that will cost you up to $100 for a CD version and $200 for the LP). That album is a catchy collection of witty, pithy introspective eruditions, many autobiographical (or seemingly so), strewn across the span of eleven songs that include an ode to (possibly the worst part of) “I-5” and the salty trucker shanty “One Brief Liaison With the Lady of the Afternoon.”

Ten years later he released his first album, Ed Haynes Sings Ed Haynes (an album long out of print that will cost you up to $100 for a CD version and $200 for the LP). That album is a catchy collection of witty, pithy introspective eruditions, many autobiographical (or seemingly so), strewn across the span of eleven songs that include an ode to (possibly the worst part of) “I-5” and the salty trucker shanty “One Brief Liaison With the Lady of the Afternoon.”

The video of the single from that crazy album, the anti-war anthem “I Want to Kill Everybody,” was featured briefly on MTV’s 120 Minutes, and the song met with college radio success as well. Other songs from that album focused on the lifestyles of the destitute and misbegotten who populated the vast underbelly of California’s central valley, where Ed did a lot of traveling for gigs. In support of the album, Ed toured extensively across the US, Canada and England.

After that, as he put it, Ed “rested on his laurels. His friends, family, and colleagues all told him ‘Ed, don’t rest on your laurels!’” But Ed followed his own drummer and “lumped this and all other kernels of advice he received into the ‘actively ignore file’ and remained a determined follower of his own, sometimes bizarre predilections.”

All laurels aside, Ed released a couple of albums in the ‘90s that failed to make of him a household name—a certifiable tragedy. He got married, and moved to Portland in 2002. He promptly released an album Snacking With a Vengeance, that received a generous write-up from the typically prickly local entertainment critic Martin Hughley.

All laurels aside, Ed released a couple of albums in the ‘90s that failed to make of him a household name—a certifiable tragedy. He got married, and moved to Portland in 2002. He promptly released an album Snacking With a Vengeance, that received a generous write-up from the typically prickly local entertainment critic Martin Hughley.

In an effort to further sabotage his feckless music career, Ed, a renowned bread-maker, opened Ed’s Bread and Submarine shop in Portland, serving “the best subs west of the eastern seaboard” for ten years, while for the most part foregoing his music. But in 2014 the indefatigable Ed first developed the concept of “The Ed Haynes Show,” his stage entity as a singer, guitarist, raconteur, joke-teller and devil may care n’er-do-well.

These presentations evolved into the stage show, A Man Walks Into a Bar: A Comedy With Songs in 2016. Lately he has returned to “The Ed Haynes Show,” with the new album A Man Walks Into a Bar Vol. 1 serving as some, though not all, of the repertoire for his current performances.

A Man Walks Into a Bar Vol. 1 is the eruditely incisive, generally hilarious, ten song account—mostly real, one would imagine, of one man’s journey through life, or as much of it as he reckons to observe. It’s amazing the situations a man finds himself in when he’s paying attention.

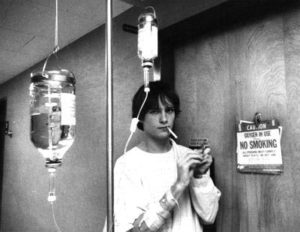

A bit o’ the Prine inhabits the cheerily morose “Hospital Bar,” which kicks off the album. Over Enrico Conedera’s honky tonk slip-note piano, and along with his own scintillating acoustic guitar accompaniment, Ed spells out the parameters of his dark premise with weary resolve: “Affiliated with no healthcare provider/Just by proxy, right next to the florist/My name is Sheila, I’ll be your server/What can I get for you grieving people/A hospital bar, we keep the high times down low/ A hospital bar— drink specials daily.”

The happy jaunt of “Grumpy Sad Hipster Baker Girl” belies the subject matter, which would seem to spring from Ed’s days as an entrepreneur of the oven. A bit of electric guitar from Mike Coykendall (who also recorded and engineered most of this project) and snappy drums from John Gannon serve to propel the story of a young woman whose general crankiness subsides for Christmas. Her story arc touches down again, later in the proceedings. Ed’s vocal calls to mind the gritty texture of the late John Stewart.

The epic “Swinging Disco Orthodontist” is everything you could possibly hope for from a song with a title like that. “I was taken to the orthodontist to get braces on my teeth/The waiting room looked like a set on Soul Train Dance Party USA/Sleek like a well-lit nightclub/Or something on TV/Set in the distant future, or in space/I took a seat by a ficus tree.”

The ensuing tale of Ed’s odd encounter with a cologne-drenched dentist, clad in disco raiment and complementary coiffure, is a drama of such upwelling vastness, it needs be heard from the bard himself to be fully assimilated.

“Good Afternoon Ferrante…Et Al.” weaves an account of mistaken identity that had a profound effect on Ed’s adolescence. “My dad bought those albums because he believed/They were the duo mom liked, but he got it wrong/He’d been misled most likely by a young record clerk/The albums he’d meant to buy were by Ferrante and Teicher/Ferrante and Teicher the easily listening piano act/among their hits renditions of popular movie themes.”

This bit of nostalgic exposition is followed by a wonderfully memorable chorus, ornamented by Ed’s rhythmic acoustic guitar and Conedera’s shimmering piano inflections. Here, as elsewhere, the mix on Ed’s vocal is dry and unadorned—no echo or reverb to speak of. It’s as if he was standing in the room right in front of you, which might be the best way to experience Ed Haynes.

Apart from their arcane subject matter, another curious aspect about Ed’s unique work is the fact that his lyrics seldom rhyme. They really don’t scan like song lyrics at all so much as phrases and paragraphs from a short story or novel. Willy Vlautin—with a sense of humor.

An exception to Ed’s easy going personae would be “SFO International November ’78,” a poignant look at a month that would reverberate throughout the Bay Area for many months and years to come.

Over some stellar, sweet guitar picking on his trusty ‘70s Takemine F365 “Guild Lawsuit” jumbo acoustic guitar, Ed’s narrative unwinds like “Taxi,” or some other serious Harry Chapin song, and his vocal performance reminds of Chapin as well.

Ostensibly set between a departure and return arrival at the San Francisco airport in that tragic month, the song recalls two horrific incidents that shook the community around the Bay Area for many, many years—even still, today. The first, November 18, 1978 was the day that US Representative Leo Ryan from California’s 11th congressional district, serving the East Bay, was gunned down in Guyana in an incident just preceding the infamous “Jonestown Massacre,” which transpired later that day.

Not two weeks later, on November 27th, San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and San Francisco Supervisor and gay activist Harvey Milk were gunned down in San Francisco City Hall by a disgruntled former employee, who was trying to get his old job back after having quit. The perpetrator, Dan White, was able to get off on a lesser charge by claiming the “Twinkie Defense,” which quickly became the subject of comedians everywhere.

Ed deftly weaves the incident into a piece of his lyric. “The man who would stand trial on two counts of Murder One/Would instead be found guilty on lesser charges/Voluntary Manslaughter, temporary insanity/Brought about in part by an addiction to junk food.”

The rocker of the set, of Buffetian/Prineian heritage one would suppose, “Mid-Level Roller,” is a satisfactory description of the typical Portlander from days of yore—before the rude outsiders came in and took over. “Hop in my mid-level roller/I don’t worry ‘bout the dings and dents/That ride’s been getting’ me to where I’m goin’ to/Since Bill Clinton was president.”

Driven by a ballsy, bluesy acoustic guitar riff, and backed again by Gannon’s smart drums and Coykendall’s amazingly effective single note on a dreamy angry fuzzy electric guitar, the groove is solid. Compact. It’s like the three of them are performing beneath the glare of a single 100-watt light bulb.

With suave irony, Ed moves to inter-relational territory in the final verse. “We got a mid-level dining establishment/A mid-sized spot for the car/So now my only questions at this point are/How am I so lucky you stuck with me/Down this pothole road so far/And are we in that magical time/A dollar off well drinks at the bar.”

“All of a Sudden Karl Malden” is Ed’s account of a close encounter with an airing of Nevada Smith on late-night broadcast television. Ben Landsverk and Jim Brunberg provide the Greek chorus behind the chronicle—one that bursts into majestic sonic fireworks at the discovery of an integral character in the midst of an otherwise ephemerally forgettable flick. The song, however, is actually quite memorable, especially in that rousing flash at the end.

The other end of the narrative arc initially scribed earlier in the project, “Bowling Alley Boy” is much closer to a short story than to a lyric, unfolding in a linear flow. We become acquainted with a young man who, not surprisingly, works at a bowling alley: with a reasonable record as an employee it would seem. Ed goes to great lengths to note in minute detail (“There’s a party of five on Lane 42/They place a complicated order—he gets it wrong”) the overwrought vagaries of our Everylad’s existence. So, by the time things begin to go awry, one has become emotionally invested.

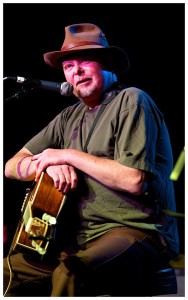

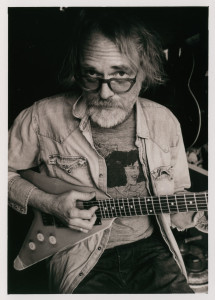

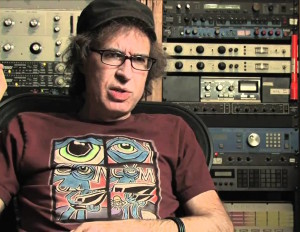

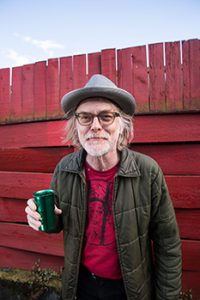

photo by Jason Colston

The arrangement gets the full treatment, with Conedera’s gauzy organ patch, Gannon’s drum, and Paul Trubachik on bass, as well as a sizeable vocal ensemble for backing in the choruses all adding to the glitzy bowling alley ambience. And as the Cascade Lanes close for the night, and Bowling Alley Boy sweeps up, the entire passion play of A Man Walks Into a Bar Vol. 1 is consummated in typical Haynesian fashion, wherein the mundane is elevated to the status of celestiality. The ridiculous becomes completely plausible in what might be construed as an unexpected “happy ending.”

A kiss-off auld lang syne, “Rough Year,” earnestly mulls the passage of time, personal and interpersonal relationships, and the acquired varnish of existence, across a wistful melody that vaguely calls to mind Paul Simon’s “American Tune.”

Finally, an incident of no particularly great significance is treated like the Hindenburg disaster in “Grain Silo Stainless Tank,” a shaggy dog story that lacks only a dog to complete the circuit. The things a guy will put himself through just to get a beer.

Were I to post them here, the lyrics of this song are so long and convoluted that the length of this review would easily double (something I surely would have done in the 2 cents-a-word Two Louies days). Shakespeare wrote several plays that were shorter.

That in no way lessens the enormity of the situation portrayed. There are moments when the arrangement briefly explodes: surrounding the phrases “condescended to,” “leaning awkwardly over a non-pushed in stool,” “unless I fuckin’ Google it” and “I was startled by the formality,” images deeply embedded in the awkward sluice of Ed’s uneasy experience. The sense is that he did not return to the establishment in question.

It’s sad that Ed Haynes did not include a lyric sheet with this CD, although perfectly understandable in that it would have had to be a 16-page booklet that probably would have cost more to produce than the rest of the package, disc included, altogether. But the lyrics and Ed’s ironic delivery of them are an intrinsic part of his presentation.

He’s a real good guitar player, with a deft touch. He’s a singer of the aforementioned vernacular, able to hold his own against any of them. You recognize his raggedly ironic voice the moment you hear it. His melodies are familiar and accessible—but, in reality, they only serve as soundtrack coloration to the musical screenplays he sets forth. And it is that precision with the setting of a scene that sets Ed Haynes apart from most other folksingers today. You’ve probably never heard anyone quite like him.

February 2019