Port of Morrow

Port of Morrow

Aural Apothecary

It’s been five long years since James Mercer and his band the Shins released the Grammy-nominated Wincing the Night Away. In those intervening years Mercer (that’s Mister Shins to you) divorced his longtime band mates and set off on numerous musical adventures. Those took him all over the world, real and conceptual. With the release of Port of Morrow, we find James Mercer exploring a deeper sense of introspection. His insights are now more resonant and mature. And now he is armed with a new batch of songs and a new bunch of Shins to help him play them live. Cool, right?

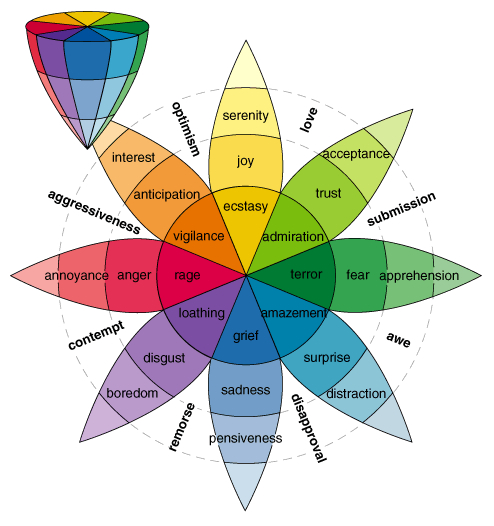

So in today’s lesson, students, we are going to study the fine art of the musical hook. What is a hook you may ask? In music, a hook is anything that drags you kicking and screaming into a song. Hence the fish allusion. You’ve been getting reeled in by hooks since your parents were kids. Hell, even “Silent Night” has a hook. Several of them actually. First one is “all is calm.” Second one is “sleep in heavenly peace.” There you go.

A hook is usually some unexpected turn in the music of a song. It might be an instrumental phrase, a lead line, a riff. Or it might be some slight change of course in the melodic bearing of a song (ala “Silent Night”). A hook can be a little thing, but if it’s a good little hook, you’re going to get caught all the same.

In the broad scheme of things, the whole era of the popular song has been dominated by hooks. The early blues and the ragtime jazz days of the early 20th century. The smooth days of big band jazz. All the Cole Porter/Irving Berlin standards and everything in rock ever since. Hooks.

I guess when you get right down to it: all music is based on hooks. You are attracted to your favorite songs or pieces of music because of them. You recognize them instantly because of them. Hooks. Beethoven’s Fifth: Dun Dun Da Dun. Hook.

A lot of hooks come in the chorus, the memorable part. Sometimes you’ll find them in the bridge. Guys like Thom Yorke have the ability to write songs with endless chains of them. That’s a real gift. Still, think of your five favorite songs. The guess is that you can pretty much sing the lines you love the most from each of them. Hooks, baby.

And why are we investigating the Art of the Hook today? Well, I’ll tell you why. James Mercer, that’s why. That guy throws out some serious hookage. Unique. Memorable. When you recognize a song as an old friend the second time you hear it in your life, you’re getting hauled onto somebody’s boat. In this case it’s James Mercer’s and it’s a forty minute tour aboard the tiny ship, the Shins.

James Mercer excels in two aspects of musical hookery. He has the intrinsic ability to craft instantly familiar songs, siphoning bits of melodies and themes from hundreds of sources that went before, stretching back over the preceding forty or fifty years. He is also very strong at creating unexpected, subtly sumptuous rhapsodies at the very moment the momentum of one of his familiar themes begins to lag. That sort of artistic intuition is quite rare, and it’s a songwriting strength for Mercer.

The first cut among the ten found here, “The Rifle’s Spiral” has a momentum and feel very similar to Arcade Fire’s “Ready to Start.” A sense of urgency pervades as the driving beat (James did his own drumming on this track) pushes the arrangement forward.

Mercer’s lyrical perspective reflects a certain quiet desperation: “You pour your life down the rifle’s spiral.” When he sings that line, it sounds as if the subject is descending down a rabbit hole of some terrible consequence. Musically, the melodic hook is pretty instantaneous with a neat little minor third ascending interval in the opening line. You will like and remember that interval. It’s inevitable.

The segue section, not really a chorus, is memorable for it’s majestic musical architecture, and the careful precision of the instrumentation. Lyrically, one can almost put together a story, though vital details seem hard to decipher in the telling. It is possible that Mercer is addressing the song to an unborn child regarding the experience of being born, though that interpretation could be far from the mark.

The first single off the album, “Simple Song,” is already receiving mainstream airplay, so perhaps this is the song to break the Shins to the public at large–out of the indie eddy and into the mainstream. Who’s to say?

Guest drummer Janet Weiss provides intense Moonian drum volleys to the lurching power-chords of the intro, which sound like an amalgamation of Tommy-era Who condensed with a Phil Spector Latin feel reminiscent of “He’s a Rebel” or “Spanish Harlem.” The verse, with James intoning low resonant notes (before leaping an octave to the customary upper register in the second verse), could be something you might hear from Beck’s Guero period. This is all part of Mercer’s knack for the “gee, I’ve heard this somewhere before” hook.

The bridge is where his ability with a melodic hook takes over–with the line “I know that things can really get rough/When you go it alone.” That section will be running through your mind for a while after you hear it, especially the “a-low-oon” melisma (I’m still trying to place the origin of that familiar little trill). With variations on two hook motifs in a single song, one may safely proclaim: It’s a hit!

With a memorably pretty keyboard intro, the gorgeous golden luster of “It’s Only Life,” conjures Sea Change Beck and Hunky Dory Bowie in the verses, before launching a luscious falsetto chorus entirely worthy of the Thom Yorke of OK Computer days–and then into the pretty singalong section of the back half of the chorus, singing “It’s only life, it’s only natural.”

From there on, it’s just a recirculating series of those choruses, broken by a totally cool spaghetti western guitar low-string guitar solo– as if the song wasn’t infectious enough. This one is a home run. And James touches all the bases.

A Latin feel invests the soul of the verses of “Bait & Switch” before turning quickly toward Andy Partridge territory in the jazzy middle sections. Another twangy guitar solo more or less continues what was established on “It’s Only Life.” It’s a tidy little number. Over before you know it.

“September” is James Mercer summoning threads of his own musical history to weave a rich new tapestry– a plaintive hauntingly joyful tune. Again he evokes a sense of birth in the mood of the lyric, like a song of newborn infancy. The western country cradle in which the song swings makes of this one sweet little ballad.

What would be another great choice as a single, “No Way Down” features all the stalwart charms that James Mercer imparts to his music. Boiled down this would amount to an endless chain of nice changes, culminating in a really memorable chorus (I can name that tune in three notes). And in the bridge appears one of the better lyrical lines of the album: “Make me a drink strong enough to wash away the dishwater world they said was lemonade.” Try to wrap your mind around that one and report back later.

A Knopfler sensibility informs the guitar solo intro of “For A Fool,” where a laid-back country feel notions a direction, again reminiscent of Beck circa Sea Change. The Beck references are not by accident but are a result of the input from multi-instrumentalist co-producer Greg Kurstin, who has worked with (besides Beck) a veritable Who’s Who of music greats, beginning with Dweezil Zappa (Kurstin was twelve at the time) and including Flaming Lips and Foster the People, to name but two out of dozens and dozens. That is to say, beyond Beck, you can definitely hear elements of everything else as well. It’s a rich musical soup, to be sure.

The melody of the verse of “Fall of “82,” a song Mercer dedicated to his sister, refers liberally to Joe Walsh’s “Life’s Been Good,”with maybe a faint hint of the verse of Thin Lizzy’s “Boys are Back in Town” thrown in for good measure. A totally ’60s trumpet solo puts the cap on this one.

“40 Mark Strasse” refers to a street frequented by young prostitutes near Ramstein airforce base in Germany, where Mercer spent some of his youth with his family. The song is fittingly eerie in context, with banshee keyboard moans graying the background behind a solitary acoustic guitar. A fairly mundane verse gives way to a sumptuous chorus that makes the trip completely worthwhile.

The title track, which references the tiny port on the Columbia near Boardman in Morrow County, is a smoky bluesy jazzy sort of number with burbling keyboard sounds, synth strings and Mellotron, and what sounds like a guitar through a Leslie speaker, but that could just as easily be a patch on a keyboard too, one would suppose. An endearingly pastoral end to delightful tour.

In literature and in painting, to be sure, it is considered appropriate and even proper to quote or copy pieces that went before. Half the books written in the English language quote Shakespeare one way or another. The pose for Picasso’s Les Demoiselles D’Avignon owes in part its substance to the work of El Greco. Classical composers constantly borrowed themes from folk songs or from other composers to sew into new cloth.

But in pop music, the idea seems anathema, even though all of rock and roll is founded on a mere handful of chord progressions. Music is everywhere to be found, to be absorbed and recirculated. Hell, as a child, Mozart claimed to hear music in his oatmeal. One hopes there are no copyright infringements pending on that one.

But all melody in music is relative. Quoting other songs, even distantly, even unintentionally, is an indication of how liquid our society is. The past sixty years of the genre are readily accessible on the radio or the internet.

A truly talented composer can use this rich palette to his advantage, by drawing (possibly unconsciously) from all of these millions of songs to add rich referential context to a tiny three minute piece of fluff. Somehow, a song acquires a gravity and density through the incorporation of only a few notes. A hook emerges. A hit ensues.

James Mercer is a truly talented composer. His ear for a hook is impeccable. Every song among the ten here stick in one’s brain like gum on the bottom of a mental shoe. Every song sounds instantly memorable, even on the first listen. And listening to this album is like welcoming an old acquaintance. Warm and familiar.

Port of Morrow is not going to overpower anybody with its lyrical insights. Mercer can turn a phrase, but he sometimes wanders away from his topic, in search of a clever line or nifty rhyme. But as pop songwriters go, he’s Grade A. He is a song fisherman of the highest order. He’s got all the hooks he needs.