Chris Newman’s name came up last time in my review of Mike Coykendall. Chris has been a very busy fellow over the past year or so. I wrote about his self-produced (on his trusty Teac 4-track) album King Shit last January, and included a review of his previous album, Beachcomber (produced by the legendary Jack Endino) released in May of last year. So between the twenty-nine songs dispersed across those two records and the fifteen here, we’ve got two score and four. And with the recent addition of an 8-track machine to his studio arsenal, there is every reason to believe there will be more from Chris very soon.

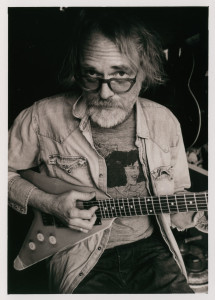

But Nobody was recorded on the 4-Track and sounds like it (that’s meant to be a compliment as much as a criticism). As on the previous outings, Chris, plays the guitar, occasional piano, a couple of harp interjections, and an organ pad from time to time. He’s again expertly supported by bassist Nathan Jorg and Doug Naish on drums. And, as with King Shit, the arrangements are pared down and primitive. There’s not much room for a lot of fancy-dancy overdubs, tricky punch-ins, or doubling here. It’s mostly live to tape. Raw and real.

Chris isn’t reinventing the Newman wheel here. His influences remain at the forefront, really no different than they were when he first got rolling 35-40 years ago (at this stage of his career he stands as one of those influences: as launcher of the early grunge ships). But he presents his songs in such a variety of styles, from blues to psychedelia, any Chris Newman recording is a real sonic adventure. And there are always nuggets to be unearthed in the program—and this instance is no different. In fact, there are many inspired performances to be found.

The album begins with the languid “Castaway,” which seems to pick up the narrative thread that left off on King Shit. The verse traverses ground similar to the Beatles’ “Happiness is a Warm Gun,” until midway, whereupon Chris launches into an elephantine solo, his guitar emitting a great pachydermic wail. Oh yeah!

Vocally, Chris fuses Captain Beefheart with Fred Cole, exorcising his dark interpersonal demons on “Drivin’ Me Mad,” while paving a black-top, two-lane grunge highway on guitar that drives hard from here all the way back to Status Quo’s “Pictures of Matchstick Men.”

The prototypical primordial grunge of “Homo a Go Go.” Thick, churning clouds of guitar hover low over the brimstone collision between human introspection and a fast-changing species. Joy Division meets Interpol in a dark cavern. Sublime. The rueful ballad “Bad Television” arrives, full circle, at the other end of the musical telescope, recalling “My TV,” a gem from Chris’ days with the Untouchables at the beginning of his career.

But where the former was a bit of a cheery ode to the companionship a television occasionally offered—the new song affords a far darker view. “I blame bad television, in all its encompassing nature.” Much has changed since Chris wrote “My TV” thirty-five years ago, the cultural landscape since laid to waste is starkly captured here. A touch of moody cocktail piano adds just the right touch of cynicism to the presentation.

“Elsewhere” is a bit of Floydian psychedelia, circa the Syd era. There’s a shadow of early Who hanging over the production as well. Chris invests a Leslie-like tremolo to his mournful solos, a tone that fits the ‘60s mode to a T. The moody psychedelia continues with the spacy, somnambulant ballad “Rings of Saturn.” Chris’ sparse, soaring guitar leads conjure Explosions in the Sky in scale of epic sonic majesty.

Jimi Hendrix watches over “Cryin’ All the Way Home,” a moody, bluesy number with incendiary solos, and banshee harp interjections, delivered over Naish’s rock-solid beat. Chris’ stinging, whipsmart fills fall somewhere along the line between Jimi and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Yow! The ghost of Jimi returns for “Deadman Blues,” with Chris firing off blistering solos over a “St. James Infirmary,” “House of the Rising Sun” setting. The nasty, roadhouse blues “Cleopatra Don’t Mind” is buoyed by Chris’ jazzy barrelhouse piano. Low, dirty vox spell out a tale of some gray, brooding voogum.

Following that extended blues interlude, the mood returns to lurching sludge with “City on Fire.” This time the keyboard ornamentation of choice is a smoky organ, but the guitar burns hot lead, distinctly maintaining Jimi in the arc of its manifestation.

A brusquely unique nylon string acoustic guitar propels “Dreamworld,” an energetic, ‘60s-informed rocker with a familiar turnaround. The focus here is lyrical. Though the vocal is buried just enough to make the deciphering of the lyrics difficult, the sense is that Chris is experiencing a great deal of confusion in his life, not all of it of his making. This song is a nice departure from the others.

The title track slaloms a hard driving two-beat, sliding downhill at a breakneck pace, until it tumbles into a heap momentarily, before resuming its cartwheel descent. Vocally, Chris occasionally invokes the wry Beefheart croak, a jagged broken windshield at other times.

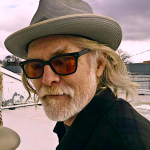

Chris Newman is a musical treasure. His significance within the Portland music scene (and well beyond) cannot be overstated. And while Chris has experienced fallow times in his life, he is now undergoing an inspired period in which he is producing high quality material on a low-budget.

In bassist Jorg and drummer Naish, Chris has found solid support, similar in reliability to the olden days of Napalm. Justifiably, Chris has bemoaned the paucity of attendees to some Deluxe Combo shows. But the truth is that so much of the population in Portland is new to the city, recently arrived, that the sense of history once so highly valued within the local musical community has dissipated.

There is good music everywhere to be found in this town, the relative importance of one act against another is such, that older musicians often fail to attract a younger demographic that might actually enjoy the artistry, if there was any real name recognition. For some genres, the blues, for instance, the demographic in this city is aging right along with the chief proponents—well, it’s the old story of the spirit being willing but the flesh (and the pocketbook) being weak.

Chris Newman merits wider recognition. It seems so odd to even be making that statement, over thirty-five years into his career, but there it is. He is certainly still relevant, still cranking out great songs at a pace someone one-third his age would be hard-pressed to rival. But he is decidedly unglamorous.

Chris Newman merits wider recognition. It seems so odd to even be making that statement, over thirty-five years into his career, but there it is. He is certainly still relevant, still cranking out great songs at a pace someone one-third his age would be hard-pressed to rival. But he is decidedly unglamorous.

Glamor and image, increasingly, seem to be what the denizens of New Portlandia crave most. Of course that’s entirely at odds with the very qualities that drew them to a backwater hardscrabble burg like this in the first place. The image of the “artist” that attracted the Nouveau Upwards here has drawn so many to Portland that the newcomers are now crowding out the “artists” they came to be among. That worked out well.

October 2015